By Emily Weedon,

She lived in Laaksolahti and hated it. She hated the suburban, fussy strangled feel to the place. Dirt roads, for Crissakes, and a suffocating amount of greenness. Overly polite but distant neighbours. Nothing to do all day but watch her daughter from the vantage of the carpet.

It was too far to take transit just to go have an afternoon play-date in downtown Helsinki with some other expats. And wine if she was lucky. Although a couple of glasses of wine meant she’d start complaining, and she’d come to realize no one cared to hear it. Two hours downtown, two hours back, a cranky kid, and light failing long before she got back home in time to make dinner. Only to wait and see if tonight was the kind of night that her husband might surprise her and be home for dinner.

More likely: dinner made, left on a plate, kept warm. Daughter asleep without his kiss. And the eerie silence of a sleeping house.

If he came home, he usually left predawn. Sometimes there was evidence: a dented pillow on the couch. She made her daughter’s breakfast and scraped a dried, untouched dinner into a compost bin.

Downtown beckoned, full of enticements. Full of bright people who spoke tinkling English tinged with so many consonants and swooning vowels. They punctuated their speech with ear-catching Ja-ja!s which were sucked in on an in-breath, as though in a moment of being caught off guard by delight. The first fifty times she heard it, she read it as a glitch. But no, this was a thing here. People sat around on patios even in winter, under heat lamps, wearing blankets, being smart and erudite. But she sat by a stove in Laaksolahti, illegally streaming Canadian Netflix, rewatching sitcoms from the 90s, nursing a fourth glass of wine. Justifying a fifth. Washing half the dregs of the fifth down the drain with sick guilt.

He didn’t want it to be over. Finland. Not the relationship, it was never about that. They loved him here. They loved how hard he worked. Next year, if he got kept on, he promised they would move to a cool apartment. With double doors opening onto a Juliet balcony. One of those turn-of-the-last-century places with soaring ceilings and molded plaster and herringbone floors. He had promised for three years.

He took side trips to Slovakia, Austria, Spain. One time he went leaving nothing in the bank and $200 Canadian cash to squeak by on for two weeks. She took riveting side trips to the Supermarket. Or for a change of pace, the drug store. But visiting a drug store for “kicks” was not the thing pushing her out.

They could have landed in Spain. Sun-splashed days and trips to vineyards and beaches and an explosion of art and architecture. Instead, long, long nights, deep, deep snow and this tick-tick language of light consonants. Hard to parse. Hard to get inside of. Maybe in Spain she could have picked up the language, made friends, gone to galleries, clubbing. Or had a ragged, idiotic affair. A fast fuck sometime. Presumably the Finns did that too, but it was hard to believe in passionate torrents riding just under their crisp surfaces. She wouldn’t mind being proven wrong.

Who was she kidding?

She was a housewife, with nothing to say, whose days were measured by meals.

Who in the history of the world would ever again fuck her?

She had left everything in Canada behind for the “excitement” of abroad. The thought of learning that loopy language had, at first, filled her with determination. Three years on, she struggled to separate the hellos from the goodbyes. With no one to talk to, how could she learn to talk?

Her language centre and her lust for expat life was done, cooked and left overnight in a warm oven. It wasn’t just that she was alone with their child in their forest house. It wasn’t just that other expats seemed to thrive on the busy beat downtown or went out with each other to night clubs or restaurants. It wasn’t just that he was never home, or available for dates out, or willing to talk about anything, or awake for more than fifteen minutes after getting home. He wasn’t willing to discuss her going to community college or getting a nanny so she could work. He sneered at the idea of a part-time job, maybe in his office, maybe filing? Making coffee?

He hadn’t hit her or anything tacky like that. That would have counted as touching and touching had not happened except on her birthday twice and at New Year’s once. If they met in a gloomy hallway on the way to the bathroom, she had to lean back against the wall to let him lumber past. She wasn’t sure how that had become the standard, but it had. A few fights had ended in a short hotel stay and a wordless freeze. A few dishes tossed out the closing door which landed without a sound and made a cartoon poof in a fluffy snow drift.

In the fluffy snow of a cozy Helsinki suburb, no one can hear your dishes break.

He was there, that was supposed to be enough and if it wasn’t enough then it wasn’t his problem. She was a problem solver, back in the heady, old days of Before Child. She was a go-getter.

She decided to solve the problem and go get gone.

She drove along Pitkajarventie until it became the Rajatorpantie, then merged up onto the 120 and relished the sight of barren highways over choking nests of trees. One bag for each of them. Carry-on only. Only the favourite three Lovey-dovey toys. She would buy new toys at the airport. They would hold her interest for longer.

The Tourist Pilot Hostel was close to the airport and very cheap. She had money but was disinclined to spend it. This wasn’t a vacation. This was surgical. The Hostel had a parking lot, a luxury in this land of old cities and narrow streets and excellent transit.

She had timed things to arrive late at the hotel and leave early. Any longer might have raised suspicions. A jab in her breast made her realize though, in a normal relationship, her absence would be noted, hard, immediately. That was normal. It wasn’t normal to be able to slip away with no email or phone call and be unnoticed for hours.

“You know I am a weekend dad!” he had screamed at her once when she asked if he would be the one to fold her laundry for a change.

She was going home. She needed to see where they had buried her mom in her absence. Once she was over there, she could “decide” to not come back. Through inertia, he’d stay in Helskini, and custody would be a pain so he probably wouldn’t bother.

The ugly face of the Tourist Pilot Hostel was “enhanced” with some oversized planters, which this time of year had nothing in them, in advance of the endless winter settling in.

“Come on. Let’s go.” She barely recognized her own voice anymore, always strained, always rushed. How many millions of times had she said that to her child she wondered, as she held open the back car door. The child was sleepy getting out. Her boots and coat were crammed over her pajamas. She waited, hoisting bags that bit deep into her shoulder while her daughter took forever to get out. “Let’s go. Please.”

Mercifully, when The Tourist Pilot Hostel doors closed, they shut out some of the chill. There was plenty of chilliness inside. The man at the front desk looked up and with dead eyes gave them a brisk nod that communicated an utter abhorrence of having to say a single word of welcome. It was so brisk, it verged on being a tic. She slid over a passport and a credit card. He pulled up a booking. Slid over a plastic key. Another tic. Not a word spoken. Her child rubbed sleep into her eye. No warm response. Anywhere in the world she ever went with this kid, people gushed over how cute she was. Not here. The chilly concierge looked right through both of them and couldn’t muster a closing tic.

She’d chosen the place for reasons beyond price. A restaurant promised steaks. There was a pool and the ubiquitous sauna. Two beds in the room—because her daughter kicked. A quick drive to the rental place…abandon the car…shuttle to the airport. Fly out to that abomination of a hub in Frankfurt and hope not to get frisked by guards for once, land in Chicago, home to Toronto. She was exhausted just thinking about the many steps.

The pool was calculated. It was a bribe and a coping tool. Her daughter would be delighted and then mercifully exhausted. There was a chance she might sleep on some legs of the trip ahead.

What she had not calculated was an overwhelming smell of mold. As soon as they were in the humid pool enclosure—a glassed-in space that was heavily condensed—they were hit with a wall of choking thick mold. The chlorine fought with the smell. The water was chilly. Finns liked chilly water to plunge into after a sauna. She sat on the edge, feet in, watched her daughter paddle in the shallow end. This was the first time she’d been in a bathing suit in public in two years. She could feel the tiles under her, where ass met thighs. Too much ass met too much thigh. When had she gotten big? She rubbed them, self-consciously.

The restaurant was depressing with pot lights and tiles from the seventies. She brought takeout to their room. Her daughter ate one piece of steak, all the fries and wanted sleep. Which meant she needed Billy Benjamin.

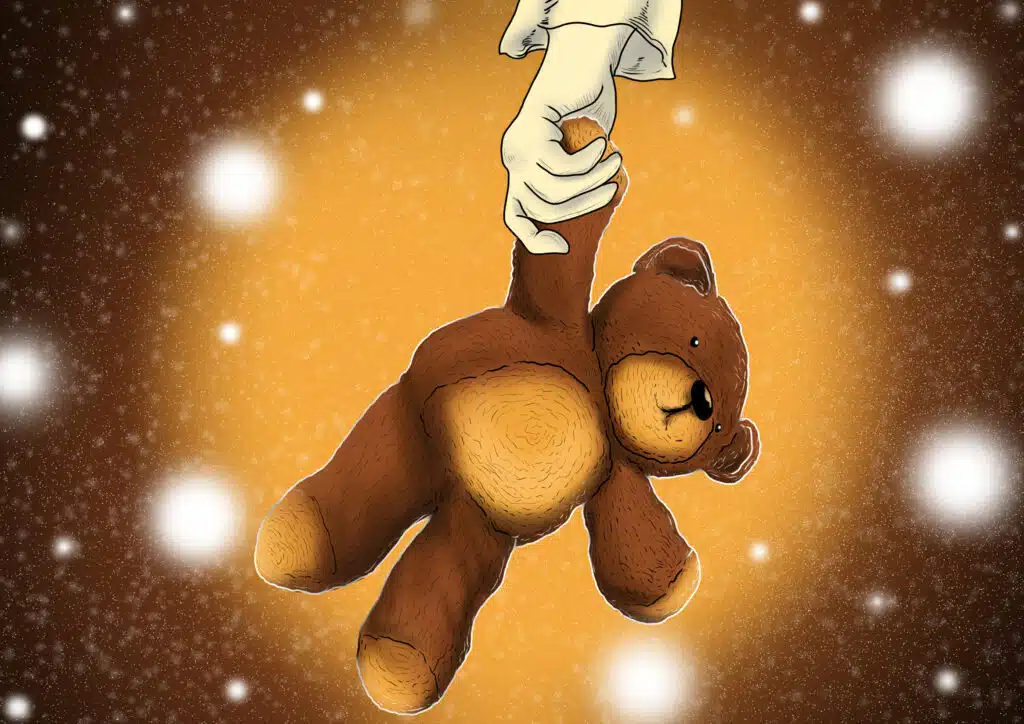

Billy Benjamin was as old as her daughter. Six years of hard love had made him into a towering point of importance in their lives. In a parenting decision which would merit therapy later, Billy never went to sleepovers, lest he got mislaid. The results would be TOO CATASTROPHIC.

Her mother crocheted the thing from old yarn. He was a misshapen bear to begin with, who only got more expressionistic with time. His face looked like the butt end of a pain-au-chocolate. He started out nearly the same size as the baby, and by now was a comfortable floppy presence clutched in her fist. He could be carried, drooping, like a sock. He won out over all the store-bought lovies and was THE Lovie. The one and only Billy Benjamin.

In a way, it was perverse that Billy was so important. Her mother, who made it, was eternally absent from both their lives. And now there was something larger than life about him, now that the hands which had made him were forever still. The poor kid of hers had a bitchy grandmother and an absent father, but at least she had Billy. She could fuck up. She could burn dinner. She could fight with her husband. Get cross about tantrums. But at least she had provided her child with a childhood lovie worthy of the love of her child.

But tonight, of all nights, when he was needed most, at the Tourist Pilot Hostel, on the lam, Billy Benjamin was not checked in.

This was no big deal, to begin with. He was in the rollie case, naturally.

No. He was not.

Fine. He was in her purse.

Again, no.

He was put to sleep in a drawer, a cute shallow nightstand drawer, before dinner.

No.

He was not in the bathroom. He was not behind the curtain. He was not under the bed. She checked the rollie case that he was still not in, again.

Now tears threatened. Not her daughter’s. Hers. Her mom was dead and she had managed to lose that one tenuous thread between them. And then…

“The car.”

Relief. She’d hurried her kid along and she had left the goddamn bear in the back seat.

There comes a few moments in every parent’s life that can never be adequately prepared for. Public bathroom. Oversize stroller. Big purse. Infant. Do you pee with the door closed for privacy while your child and purse sit in the stroller? Do you carry purse and infant into the cubicle and hold them both while you urinate? Do you pee with the door open for anyone shopping in the mall to see, since you are now merely a parent, and no one cares about your privacy or even wants to look at your now-gross privates anyway? Do you piss your pants in the car on the way home because you were too proud to do any of the above, and your bladder hasn’t come back online?

You make a choice, and you rest assured that whatever you did, it was the wrong choice.

She left her kid alone in a shitty hotel room and walked the long, stinky walk down wood-printed plastic to the car so she could get the bear, then pour a glass of something, take a pill and sleep until it was time to go. She left the tv on. As though that would somehow keep a six-year-old safe and occupied.

The bear.

Was not.

In the car.

Her stomach fell. She looked under the front seat. In the pockets. In the side pockets. In the glove box because by now she was in a panic. The floor mats were flat, but she looked under them anyway, and got rewarded with cold salty water. She looked in the trunk. She looked behind the visor. Both of them. She got on her knees in the cold, feeling wet staining her jeans. Under the car: nothing.

Mr. Chilly at the front turned baleful eyes to her, using not his neck or head, but his whole body. His eyes were milky blue, made paler by the weird lighting. He was on the plump side, hunched, wearing a sweater that defied being called any one colour and a downy beard that hugged the whole bottom of his head. He looked like a tennis ball.

“What?”

“I’ve lost my child’s lovie—her toy.”

He pointed.

She followed the point.

A sign read: “Not responsible for lost items.”

She remembered expensive hotels all over the world, honeymoon days, early baby days. Concierges who would have gotten into cage match fights with each other to make her, the customer, happy. Not Mr. Chilly.

“We must have dropped it on the way in from the car.”

“So?”

“Maybe one of the cleaning staff saw it, on the floor?”

“They don’t come in today.”

“Do you have kids?”

“I don’t see what that has to do with it.”

“This is her only one. She’s had it her whole life…”

He wasn’t just not being friendly, he was hostile. She looked past him for a moment and was shocked to see herself in the mirror behind him.

What she saw in the mirror was a disheveled, slightly chubby, yet somehow gaunt-faced middle-aged woman. As though on cue, a willowy lady arrived. They rattled off to each other in perfect Finnish.

She dropped both palms to the counter. If she was going to be discounted as a middle-aged nothing, she might as well dig in and be a bitch about it.

“Look. IF you see anything, please let me know in my room, ok. He looks like this.” She showed a photo of the bear. He gave a look calculated to be the most perfunctory.

“Of course, Madame.” The madame was for her benefit. This wasn’t the kind of place that said Madame except to colossal pains in the ass.

“Perhaps I can be of help?”

She turned and saw a gentleman wearing a burgundy jacket, his hand on Mr. Chilly’s shoulder.

“Welcome, Miss…”

“Warren.” She took his hand. This was what hotels usually felt like. That fuzzy feeling of being treated nicely. She could have been in Venice again. Or Vienna. Or Vietnam.

“I am Mr. Afamia. Tervetuloa.”

“You aren’t from here.”

“Oh, I apologize, my accent is just the worst.”

“Ja.” Agreed Mr. Chilly.

“Kiitos, Aino. Miss Warren, how can I help?”

She explained the missing bear, and its importance. Mr. Afamia slammed his hand against his heart and clutched the shirt there, looking mortally stricken. Did Mr. Chilly roll his eyes?

“My god, let’s find this bear. Nothing more important to a child.” He stepped out from behind the blonde wood desk and joined her in the lobby.

“I have seven children, thanks God. All grown now. I can’t tell you the number of missing boo boos and bears and dollies and so on. I am an expert.”

He walked with her while she retraced their steps. They visited her room first, which she was embarrassed about: it looked like a crime scene, with both mattresses on the floor. Her daughter sat in a pile of bedclothes. Mr. Afamia, rather than comment on the room, or the fact that her daughter sat there alone watching SpongeBob in dubbed Finnish, reached into a pocket and produced candies in plastic foil.

“We tore the room apart and he is not here.”

“We carry on then. Where else?”

They retraced their steps to the pool. The change room had only hooks and bare benches. No bear. The pool area had nooks to investigate.

“I have many plans for this area. As the new general manager, I want to make this place feel like a real hotel.” He swept his hands in the air. “Glass with triple glazing. Plants here. A fountain. A small pool for young children. A hot tub for old people, like me.”

“You’re not old.”

“My first grandchild.” He beamed and produced a wallet photo in a practiced gesture. “But I hope, not so old yet.” In truth, handsome. He had a blueish stain of stubble coming in through his taut skin. He was sallow now, but she imagined he tanned very dark in the summer.

“Where is your grandchild?”

“Damascus. Syria. I am working to get them out. I used to have a hotel there. A large one. In my family for generations. Big glass windows on a high street. Brass everywhere. An army of waiters and busboys.” His eyes flashed. “It looked like the Champs Elysée. But better frîtes!” She laughed.

The went back along the hallway, scanning as they walked in case the bear lay crumped randomly against the baseboard.

“I hope to replace these plastic floors.” Mr. Afamia remarked with real pain in his voice.

“That will be…nice.” She hoped she sounded encouraging.

“Perhaps next time you come, this place will be worthy to stay for pleasure, not just for the airport. I would be honoured to have you stay again. It means so much to me to have people return. Maybe next time you travel with your husband.”

“I don’t think I’ll be doing anymore travel with my husband,” she said darkly.

“In any case, you and your daughter are welcome. I crave having some kind of connection with the people who come through—because this place is so…brittle. People. They don’t let you in. Not like my home. People at home throw their doors open, their hearts open. You would meet my wife. She would stuff you with food. Your daughter would play in the garden. We had a beautiful garden.”

“I had a garden too. But it’s the talking I miss. In my own language.”

“Oh! This! This I know! Everywhere I’ve travelled in Europe, a little cold. Like the weather. At home, we don’t just say ‘good morning’ like some kind of robot. We mean it. We want you to feel it. We say Saba hal noor! Morning full of light! Or Saba hal Ward! Full of flowers! Or hal asel Morning full of honey….” He trailed off. She imagined Mr. Chilly being forced to say such things. She noticed Mr. Afamia wore a cardigan under his wool jacket. When he shook her hand, his fingers were frigid. It was a cold place they had both come to.

In the lobby Mr. Afamia got down on his hands and knees and looked under all the furniture. She caught Mr. Chilly watching with twisted lips as he did so. They passed a girl from housekeeping—so much for Aino’s claim the cleaning staff didn’t come today, that unhelpful bastard. She was a whey-faced woman who pushed a cart along the hall like Sisyphus with his eternal rock. Her lips were pressed so tight they were blanched of blood.

Mr. Afamia paused and put his hand on her shoulder. They nodded to each other. Wordless. She carried on.

They went on, scanning. Here the plastic floors gave way to broadly striped carpet. Screaming white. Bloody Red. Unappetizing brown. Garish zigzags moved woozily down the hall.

“I’m planning to replace the carpet.”

“That’s a good idea.”

“I wish I had a wife to help me with such things. I am helpless with décor.” She accepted the gentle flirt, wordlessly. It was like passing a heating vent in a cold room.

In the restaurant, he knelt at every table, every bench—even the ones with people at them. They looked in the garbages. Under the counter. Under fake plant leaves.

Suddenly she was crying.

“He’s gone. I think I left him at home and I can’t go back. My mom made him and she’s dead and I— .” One sentence, no breathing. Now she got the hand on the shoulder. The slight squeeze. And understood: ‘It’s ok. I’m here.’

He sat her on a swivel chair at the bar. He ordered her to order. She got a whiskey. Because Finns drink vodka.

“My garden,” he told her. “Best on my street. My daughters danced there. Three of them took ballet. One very seriously. My wife made parties. Climbing flowers. A fountain. My sons liked to sit with the hookah—I never did. But the smell of the tobacco so sugary—it wove through the air, got stuck in your eyes, poured down your throat, like honey.” He looked down at his hands, now sallow. “Gone now. Just rubble. Glass and brass and brick and honey and grape leaves. Rubble.”

She sipped her whiskey through a paper straw and let the brown liquor poke a hole through the clutch in her throat.

“My dear Ms. Warren, We go on. This little bear is maybe going to start a new life now. Bring some pleasure to another child. Your child is growing. Mr. Billy Benjamin will bring joy to others, as she will.” He patted her hand. “Look for the joy. Even though you are sad. We are human only when we have both.”

The bartender hovered. Another dour Finn, cold face, long-distance eyes. Mr. Afamia’s deep brown, warm brown, almost hot brown eyes with their thick fringe of kohl lashes, melted him away.

“Last night, we had a loss. In the hotel. One of the maids. They found her—” He clasped his long fingers in a knot. “She was sad. Very depressed. She hadn’t said anything. Not one word. To anyone! No one does, in this country.” He sat up, a little brighter. “Where I come from, you’d hear all about it. Someone would be tearing their shirt, howling. Breaking something. You’d know all about it.”

“I want to go home. Mr. Afamia.”

He nodded. A long slow, careful, nod which was not a tic.

“Your husband is foolish if you no longer want to travel with him. We make home for each other. Here.” He pressed a fingertip to his heart.

She returned to the room, bereft of the bear, full of guilt for the drink. Her daughter was asleep. She curled around her and dreamed of gardening.

In the morning, they left. She did electronic checkout to avoid the staff. She loaded the car while her daughter waited in the lobby.

Luggage in the back seat. She trudged back to the flat face of the hotel under a sullen sky. In three hours, they would be above the clouds. Away.

She almost walked right into one of the oversize planters in her haste.

Someone thoughtful had placed him there. It had snowed on him, giving him a little pointed snow hat. He was slumped, leaning against a dead stalk.

Billy Benjamin.

She picked him up and held him to her heart.

Emily Weedon is a novelist, screenwriter, and film producer. Her forthcoming dystopic novel “Autocrator” will be published by Cormorant Books in 2023. She has also written a collection of short stories about dating in the post-romance age of tech including the Yes You Can Contest award winning short story An Officer and a Fiction.