Father in Exile

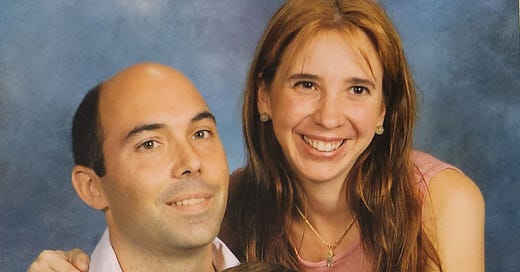

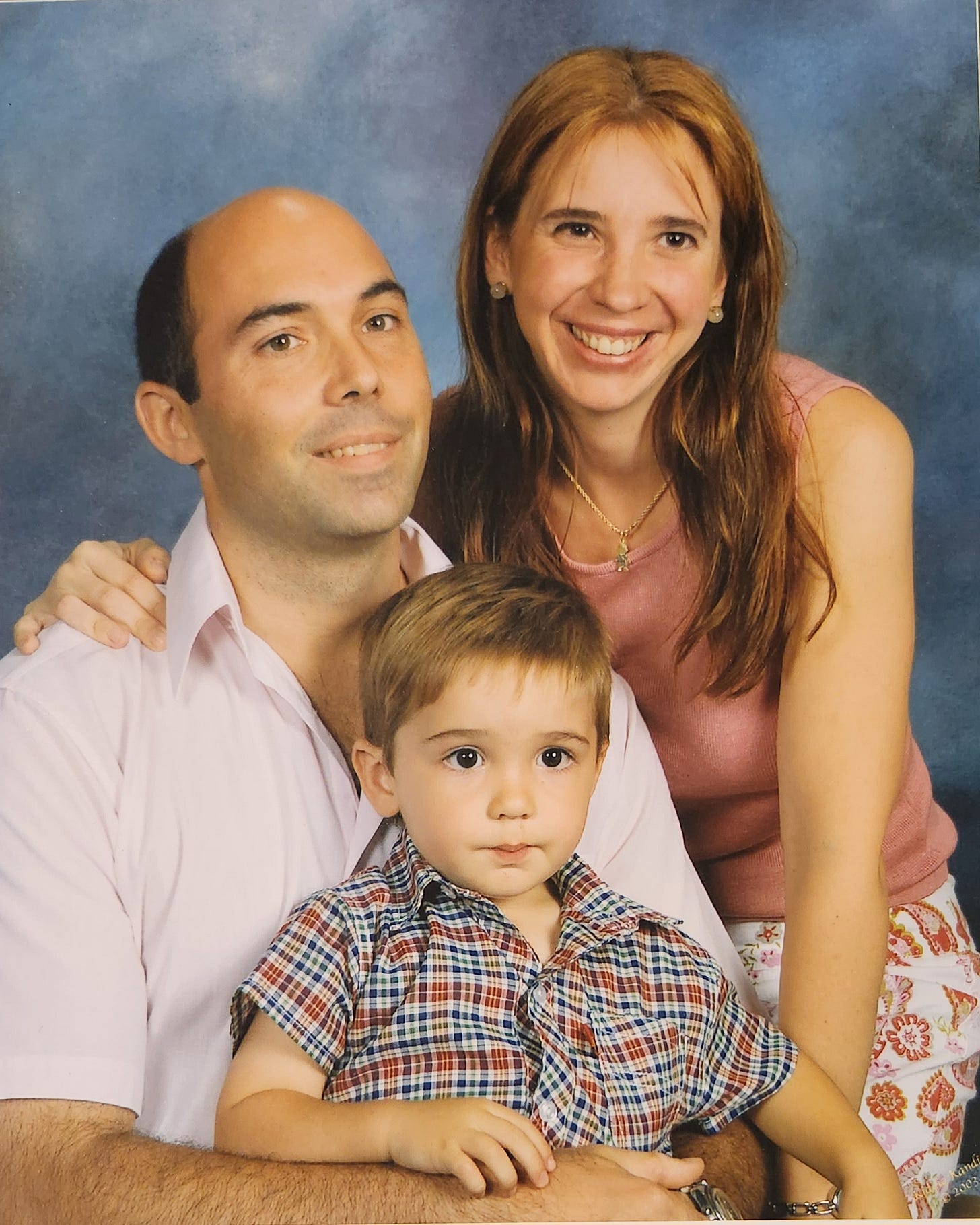

Twenty years ago today, Gilbert's wife, pregnant with their second child, took their almost 3-year-old on a roundtrip flight to Buenos Aires. She never came back, launching years of heartache.

By Gilbert Le Gras,

On October 21, 2000, I married an Argentinian woman who said that she would “move anywhere in the world for the man I love.” Maybe she just didn’t love me that much because 1,471 days later, on October 31, 2004, she boarded a roundtrip flight to Buenos Aires with our son, Olivier, who was almost three, while six-months pregnant with Joaquin, our second. Days after Joaquin’s birth in February 2005, she told me that they were never coming back.

Previously, she had made it clear that she did not like living in Ottawa where my employer Reuters moved us after my 3-1/2-year assignment in Argentina wrapped up. I wasn’t keen on moving back to a place where I had dodged bullets in Plaza de Mayo while the president escaped by helicopter from the rooftop of his palace in December 2001.

As far as I was concerned, Canada seemed to be a better place to raise kids, but I know how demanding preschoolers can be and I did appreciate how close she was to her parents and sister. There were viable, stable, alternatives near Argentina. I had applied for jobs with Reuters in neighbouring Brazil and Chile, so in late October 2004 when she packed up her things and wrote “In Case We Move” with a sharpie on those boxes, I felt the pressure.

I assured her of my confidence that after two years in Ottawa, my employer would agree that I’d done my minimum amount of time and would allow us to move back to southern South America if I got one of those jobs.

When I joined my family in Buenos Aires in February 2005, one night in our bedroom just before turning in, she explained that she and the boys were staying in Argentina “for at least a decade.” She wanted a divorce, and I should live elsewhere than the home I’d bought there as our family’s pied-a-terre in 2002.

She then rolled over and turned off the lamp on her nightstand, just like you’d discuss the next day’s assignment of chores. I can’t remember whether she said “good night” — I was so dumb struck by the fait accompli. It felt like I’d been hit on the head with a sledgehammer.

A few months later, after signing a mutual separation agreement, I moved into the guest room of a Canadian diplomat I knew from the Embassy and so began close to three years of nearly sleepless nights. I couldn’t help but think of my two oldest, closest childhood friends, both of whom last lived with their fathers when they were 5. One’s father moved to Hawaii and my friend had to go see him there when he could afford to, and the other’s father lived across town but rarely had him over. My father had become a surrogate to them both.

I applied for 18 jobs in Buenos Aires but was only able to get a 90-day contract at the Embassy of Canada, which I took to buy myself time. My full-time job in Ottawa was mine to come back to as long as I returned by the end of my agreed upon parental leave. One day later and I’d lose my job.

My first divorce lawyer suggested I leave my cell phone behind, go to the Retiro bus depot and take the boys to the porous border with Paraguay and disappear. It reminded me of Sally Field’s 1991 film “Not Without My Daughter” and I was beside myself, thinking I’d be accused of child abduction rather than what the Hague Convention labels their mother as the “taking parent”. I wouldn’t do it.

That terrible day arrived. I walked Olivier to kindergarten and watched him climb up into the school bus for a field trip and pound on the window with his palms crying out “don’t go” and I was calling out “I’ll be back soon. Everything’s going to be ok.” After the bus pulled away, I sobbed uncontrollably and the more compassionate parents who had yet to take sides came over and hugged me. I flew back to Canada that afternoon.

Meanwhile, I found a child psychologist who wisely advised me to come not once a year for a month but as frequently as possible to give my young children regular contact with me. I flew from Ottawa, and then briefly from Washington DC, and back again from Ottawa every other month in the first three years and at a gradually descending frequency since then. Total to date: 74 visits.

Still, the damage remained. Once, in the early years, while waiting for the light to change at an intersection, perched on my shoulders, Olivier asked if it was true that I’m a millionaire and there’s nothing I love more than money. I know I should have exercised more self-control, but I guffawed and blurted out “If that were true, I wouldn’t spend so much of it coming here to see you two.” Which turned out to be a compelling argument for him, but apparently not for Joaquin.

A few years later, Joaquin refused to speak with me for nine months. I would phone Sunday to Friday (Saturday being pyjama party night elsewhere) and at most he would come to the phone to say robotically “Joaquin is not home at the moment, leave your message after the tone”. I had no idea how long this would go on, but my new lawyer and my child psychologist told me he was testing me to see how far I would go and then just like that, one day for no apparent reason, he resumed speaking with me.

Finally, in 2017, applying all of his teenage moral suasion, Olivier convinced his mother to at last sign his and Joaquin’s Canadian passport applications so they could come visit me in Ottawa. I was over the moon, as were my parents and brother. A breakthrough, at last.

Olivier and Joaquin have come to Canada every July since 2017 (their academic Southern Hemisphere Winter break), until last year when Joaquin cut his gap year here by half once he established his residency, which unlocked access to his education fund. This year, Olivier brought his lovely girlfriend of the past three years with him, and she loved it. They’re both scheduled to graduate from university next June and are talking about moving up to Canada on a trial basis.

Now, I have what my peers describe as a much closer than average relationship with Olivier and I am completely estranged from Joaquin who parrots his mother’s narrative that I abandoned him and left him to live in poverty. I’ve saved C$48,000 for each of my sons’ Registered Education Savings Plans and the trips have taken their physical toll: I’ve been wearing hearing aids since last year after my 72nd long-haul flight to the southern end of the planet showed my hearing had fallen below the normal range.

The heartbreaking truth about Joaquin is I never really felt like he loved me back. I can see through his gaslighting and guilt trips but now he’s moved on to violent outbursts. What began with hitting the dog when he’s angry has evolved to choking Olivier and putting his mother in headlocks, saying he’s learned how to kill people at his kickboxing school. My wife and stepdaughter are afraid of him.

The only time he contacts me is when he wants money and despite every attempt I’ve made to set him on a better course, I’m just not getting through to him. I’ve talked with enough psychologists and other parents to realize that I’ve done everything I could that was healthy. I’ve reached a point where anything more I might do would never be enough to get us on a path towards a healthier relationship. I sometimes take solace in the story of the Prodigal Son, but I accept that there’s a strong likelihood that I’ve lost Joaquin forever. I did my best by both of them. There’s comfort in that.

Gilbert is a special advisor to a three-star general mandated with reforming professional conduct within the Canadian Armed Forces. He is happily remarried to Katharina, whom he’s known since high school in Winnipeg, and together they care for two adult sons and a 16-year-old daughter while somehow finding time to paint murals and write fiction.