(George F. Walker, one of Canada’s most prolific and popular playwrights, pens an elegy to his father in seven parts. Esoterica will syndicate one part each day leading up to Father’s Day. Read Part One, Two and Three here.)

By George F. Walker.

All over the place. Because I’m often bad at endings.

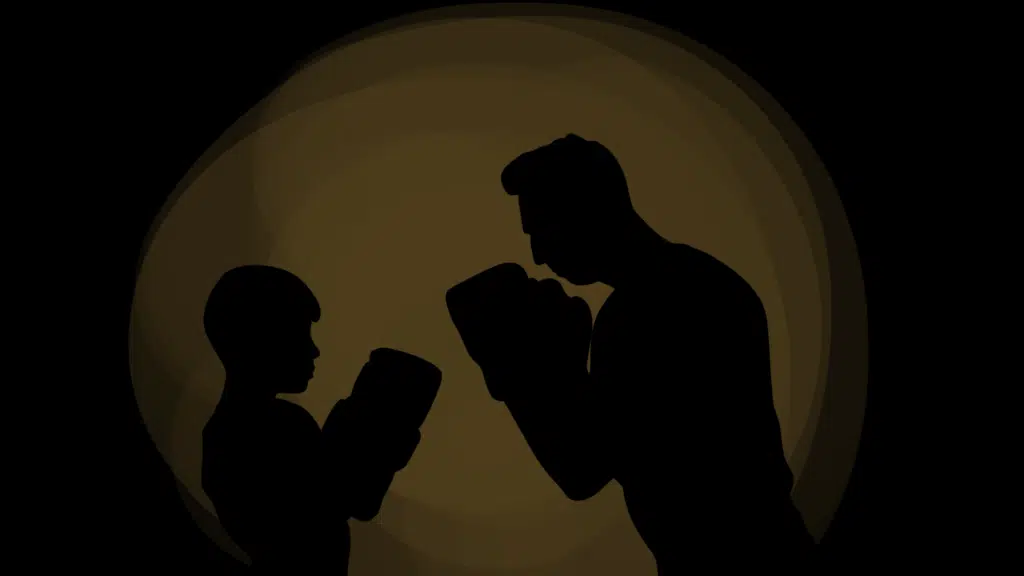

My father the fighter. A very gentle guy in a violent sport. He did it for the money. He did it because he could.

When my dad tried to teach me how to box, when I was 12 I think, all the early lessons were about how to avoid being hit as much as possible. He then asked me to press on his nose. When I did, it spread across his face like pancake batter in a hot frying pan. Because his nose had been broken so many times there was almost no cartilage left in it.

“I was slow to learn how to defend myself.”

But because he’d been beaten in a few brawls while travelling in box cars and almost killed in a couple, he knew if he was going to continue fighting, he had to come up with a style. A strategy.

One that kept him on his feet long enough to either win on points or land a punch that disabled his opponent. It mostly involved fighting southpaw with his chin tucked under his curved shoulder. And never approaching straight on. But sideways. Whatever. One of the clippings in the scrapbook referred to his unorthodox style.

So…My dad was 5ft. 9 inches and at his normal weight (about 180 lbs) he looked a little pudgy. But at his fighting weight of just under 150 lbs he probably looked a little scrawny, so guys who’d heard he was a fighter were always dismissively challenging him. In bars. Playing baseball. At family picnics. My father never responded. But one time when an uncle kept insisting, my dad first tried to warn him.

“If you come at me hard, I’m going to have to defend myself. And then if you keep coming you’re going to get hurt.”

The uncle kept coming. And he got hurt. But my dad was so upset he never (with a couple of unavoidable exceptions) fought outside the ring again. And since he accidentally gave my mother a black eye when they were play fighting, not even for fun.

A pacifist’s approach to the fine art of pugilism.

And during the war he always tried to keep in mind that it was Hitler and the other fascists he was against. Not their duped followers. Never Germans or Italians. He knew too many back home that he liked and admired.

Once when he was on leave and staying with a family on their farm in Northern England a damaged German fighter plane landed in one of their fields. My father watched from the kitchen window while he was rolling dough for an apple pie. Then he left the house and started towards the plane. Without any kind of weapon.

The pilot crawled out of the cockpit, saw my dad approaching and raised his arms. So… my dad raised his arms as well. Peace on earth. The pilot was badly shaken, and my dad was about to invite him into the farmhouse (for a piece of pie??) when a few soldiers showed up in a jeep to take the enemy pilot away. I didn’t ask him, but I’ve always wondered if my father waved goodbye.

My mother’s hell was basically every minute of the time my father wasn’t there. I can’t comprehend the depth of concern and continuous panic she was experiencing. I’m sure it was just as awful for most of the women who were left behind. But my mother had met my father when she was just 15. There had been no real life before him. She had left school when she was 12 (no one cared) and worked ever since to help her very large family. He was her freedom. Her life. Without him she felt like a child again. Except now she had 3 daughters to take care of. Not alone though. Because while my dad was overseas, she and the girls stayed with my grandma.

And she was a gift to motherhood. A slight but tenacious girl off a farm near Kirkfield, Ontario, she moved to the city to train as a seamstress. She married my grandfather after his first wife died and took over the raising of his four children. Plus, the four of her own that came along. She taught my sisters how to sew, knit and in every other way take care of themselves. While my mother worked in a weapons factory and just barely hung on.

My father on the troop ship heading home was a man between two worlds. Two lives. Maybe three. Because he still dreamt about his life as an untethered bum. No responsibilities except for feeding himself. No one else to worry about. Certainly not that house full of women waiting for him. No, he didn’t think they were helpless. His mother would make sure they weren’t. But there were men out there he didn’t trust. Most of them actually. Not with his daughters. It was something he was going to have to get over.

But there might be a few guys who needed to suffer first. He once chased my youngest sister’s boyfriend down the street when he was late, very very late getting her home. But before all that he just had to learn to be with them again.

He tried to set rules. They broke them. He tried to set rules that weren’t as strict. They broke them, too. And he confessed to my mother that he actually gained respect for them when they did it. So finally, he settled on just one rule. Never disrespect your mother. (I broke that rule once when I was in my teens and found myself immediately pinned to a wall and ordered to apologize.)

But way before that I know he mostly just concentrated on loving them. And they loved him back. Actually, they adored him. At his funeral every one of them was a mess. Yeah, he died when he was 82. In Sunnybrook Hospital’s cancer ward.

But before that there was this. He wouldn’t eat. The chemo left him without an appetite. I got a call:

“Dad won’t eat.”

“Since when.”

“Three days. He has to eat. Can you come out here and get him to eat? He listens to you.”

“About eating?”

“Please.”

So, Susan and I drove to Brampton. My father was sitting on the end of the bed.

My sister Edith was trying to get him to take a pill.

“These pills are important.”

“Are they?”

“Very.”

“Well, if you like them so much you take them.”

“Dad?”

And then from my mother:

“Mac, you have to eat something.”

“I don’t want to.”

“You have to.”

‘Why?”

My mother and sister looked at me.

“Dad listen. You have to eat something. Because if you don’t, you’ll DIE!”

He looked at me. Nodded a little. Then said.

“Okay. I’ll have a fried egg sandwich.”

Then later in the hospital there was this. The family was all around his bed. I was standing by the foot. He was not even close to being conscious when he slowly gestured for me to move aside. Mum said he was trying to see his mother and I was in the way.

I moved. And he smiled.

One more thing: About family. And everlasting love.

When my sister was dying in her bed, her children there around her, she was 92 and fading when suddenly she found her voice again and said with her arms spread out.

“I want my father!”

Man, that last line was so hard to type.

(To be continued…)·

George F. Walker is one of Canada’s most prolific and popular playwrights. Since beginning his theatre career in the early 1970s, Walker has written more than 30 plays and has created screenplays for several award-winning Canadian television series. Part Kafka, part Lewis Carroll, Walker’s distinctive, gritty, fast-paced tragicomedies illuminate and satirize the selfishness, greed, and aggression of contemporary urban culture.