A Different Kind of Homecoming

A journalist returns to Berlin to donate Holocaust related papers.

By Janet Guttsman,

In a city of memorials, the windswept platform at Berlin’s suburban Grünewald train station is particularly haunting. Just to the side of the main station, a brick staircase leads to an unused rail line, with trees and grass growing between the sleepers at one end. Metal plates on two long, empty platforms list the trains that took Berlin’s Jews to the ghettos and concentration camps of Nazi-occupied eastern Europe: the destination, the date and the number of “passengers”. A thousand Jews to Riga, a hundred to Auschwitz, 973 to Lublin in Poland.

The final trains, some with just a handful of victims, left Berlin in February 1945. Let’s think about that one for a second. Auschwitz was liberated in January 1945, the German army was in retreat, Allied planes were bombing Germany to rubble. And the authorities still devoted precious resources to shipping innocent people to their deaths. My paternal grandparents were two of the 55,000 of Berlin’s Jewish victims.

The Grünewald “Gleis 17” Memorial was created in 1998, well after most of my multiple visits to Berlin, so this was a new destination for me, and one that will stay with me forever. I lived in what was then West Berlin for four months in 1978, and I visited many times in the heady days after the Wall came down in November 1989, both as a journalist and as a tourist.

December 31,1989 remains the most memorable New Year’s Eve of my life. I borrowed a hammer to chip bits of coloured paint off elaborate Berlin Wall murals, and traded sparklers with an East German family on their side of the now partially destroyed barrier as the clocks rang in 1990. We were just a few hundred metres from the Brandenburg Gate, a symbol of Imperialist Prussia, the divided Cold War city and now of Germany’s revived and reunited capital city.

Looking back at those trips, I realize how much I have always loved Berlin, a green, lively, welcoming place. But this visit, in October 2024, was something very special. It combined memories, a roots trip and a handover of family papers to the archivists at Berlin’s Jewish Museum.

I cried. I felt as though these documents, like me, were coming home.

Let’s add some context. My grandfather, Walter Johann Guttsmann, was born in Berlin. He studied engineering there and served in the Kaiser’s army in World War One, with a posting in the Vosges, one of those parts of Europe that was French one decade, German the next and then French again.

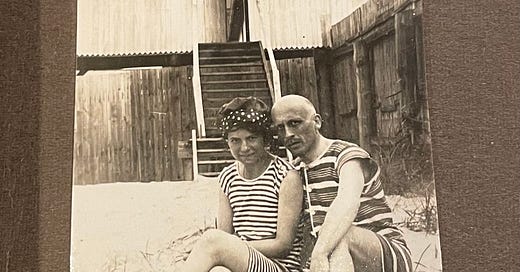

Just after the war he married fellow Berliner Helene Kamarase, and the couple settled down to a normal, middle-class life. Apartment in Berlin, weekend cottage in Werder, just outside Potsdam, two children, Willi and Hannah. A Jewish family, yes, but German to the core. Those documents I gave the archives included a yellowed newspaper supplement from 1928 in which Hannah, blond haired and pigtailed, poses in front of a traditional Christmas wreath.

Then the Nazis came to power. Walter lost his job at the AEG engineering plant and the family moved from Berlin to Werder, making the weekend cottage their permanent home and trying to avoid the escalating antisemitism of the capital. But even in sleepy Werder, life for Jews got relentlessly tougher. The kids were kicked out of school and Willi trained as an agricultural worker in the hope of emigrating to Palestine.

Hannah, still a teenager, did leave for Palestine and then Willi got a rare visa for Britain where he worked on a farm in Scotland and met my mother, a Jewish refugee from Slovakia. Desperate to leave Germany, Walter and Helene shipped a container of family goods to Sweden and learned Hebrew in the hope of following Hannah to Palestine. But the war killed that chance, and the authorities forced them to move from Werder to Berlin, first to relatives, and then to a crowded Jewish apartment.

And how do I know all this, given that my father rarely talked about his childhood and mentioned only in passing the time he spent in a German concentration camp after the November 1938 Kristallnacht pogrom? Because of a family archive, boxes of paper that include poems and love letters from the 1910s, postcards from family vacations in the 1920s and 1930s and correspondence that went on deep into World War Two.

Unusually it’s a virtually complete record of wartime correspondence – incoming and outgoing letters between parents and children – because Walter gave a box of papers to a friend before he and Helene were deported and those documents survived Berlin’s end-war bombing and destruction. The last letter to the children from Berlin is particularly chilling, as the couple mulls that their so-far “relatively free” existence is coming to an end.

“Tomorrow we are heading into uncertainty, and a very uncertain, difficult future,” Walter wrote.

I took most of the papers back to Canada when I cleared out my mother’s flat in Britain and I kept them much as my parents did, buried in a box of things I didn’t want to think about. Yes, I read some letters from time to time, focusing on the typewritten ones from 1940 and beyond. But I never could read my father’s handwriting, and it turns out that his father’s writing was even worse, so I gave up and put the bundles back in their forget-me box.

Fast forward to spring 2024 when German friends visited Werder and sent me pictures of tiny memorial stones embedded into pavers on the driveway to that Werder house. I think my heart stopped beating. I need to see these, I thought. And while I’m there, let’s find a home for the documents because I know I’m never going to read them. What better place than Berlin’s powerful Jewish Museum, which tells the history of Jews in Germany and Berlin, including the dark, dark years from 1933 to 1945?

Museum chief archivist Aubrey Pomerance responded with an instant yes when I emailed to ask if the museum was interested in giving the documents a home, and my maybe trip was on, with a librarian friend from Toronto tagging along to help.

Aubrey was a warm, welcoming guy, a Canadian from Calgary, who definitely appreciated the gift of maple syrup we triple wrapped for the trip. (Neither of us liked the idea of maple syrup seeping onto already fragile onion-skin papers.) And Aubrey seemed genuinely pleased to get the documents, which will be catalogued over the next year or so and then made available for the world to see.

He added context at crucial moments of my summaries of family history, questioned some of my assumptions about timing and shot down my concerns about my grandfather’s role after he was deported from Berlin. Two months after arriving in the closed-off Piaski ghetto in Poland, Walter, a German-speaking former soldier, was named a member of a new Jewish Council that oversaw ghetto affairs and did the Nazi’s bidding (the previous council had been “resettled”). It’s a questionable role that might have given him God-like powers on who lived a bit longer and who died sooner. Aubrey cut my speculation short. “He had no choice,” he said.

The document handover was the hugely emotional highlight of a week-long trip to Berlin, which also included reunions with bits of the city where the Wall used to be and a train-train-bus trip to Werder, where the little memorial stones to Walter and Helene are almost invisible at the edge of a dirt road to nowhere. There are tens of thousands of these Stolperstein stumbling stones across Germany and Nazi occupied Europe, each one marking the last place where a victim lived of his or her own free will. The ones we saw on Berlin’s streets are shiny brass. These two are almost black. Sadness upon sadness.

They don’t mince words. “Here lived Walter Johann Guttsmann, born 1880. Involuntarily relocated to Berlin in 1939. Deported to Piaski in 1942. Murdered.”

That brings me back to the Grünewald memorial, where fallen leaves covered some of the endless lines of metal plates. Walter and Helene were two of the 973 Jews on the one-way trip to Lublin, Poland, on March 28, 1942 and then on to the ghetto in Piaski, a little town to the southeast. I don’t know if they died in the ghetto or in a Nazi death camp like Sobibor. It doesn’t matter.

Walter and Helene were among the countless victims of that terrible war. I gave away their letters in the hope that they and their story will never be forgotten.

Janet Guttsman lives in Toronto where she rides bikes, makes jam and enjoys long walks in the city and beyond. She worked as a journalist in Britain, Germany, Russia, the United States and Canada and occasionally wonders if Berlin is her spiritual home.

The post A Different Kind of Homecoming appeared first on Esoterica.