Spreadsheet People is the winner of Esoterica’s inaugural Short Story Contest.

By Emily Zasada,

It was a Monday afternoon, and the spreadsheet people were at it again.

Sara had the quarterly budget open, it had been open on Friday, and now it was open again, damnit; there was no escape.

Also, if it wasn’t this quarterly budget, it would be another one from another quarter; they were all the same, pretty much. She was copying and pasting her formulas from one cell to the next, thinking (as she usually did) what a slippery process this was, how easy to have one cell reference wrong somewhere without knowing it and then have that wrong reference transposed to multiple cells, all without knowing it, because there’s something so deceptively smooth about the copy and paste process with the way it just leaves a fresh number in a cell calculated by the underlying formula and, honestly, who wants to go back through and double-check everything. Who doesn’t just want to call it a day, believing that those numbers are correct?

She was halfway through what she was doing when they arrived.

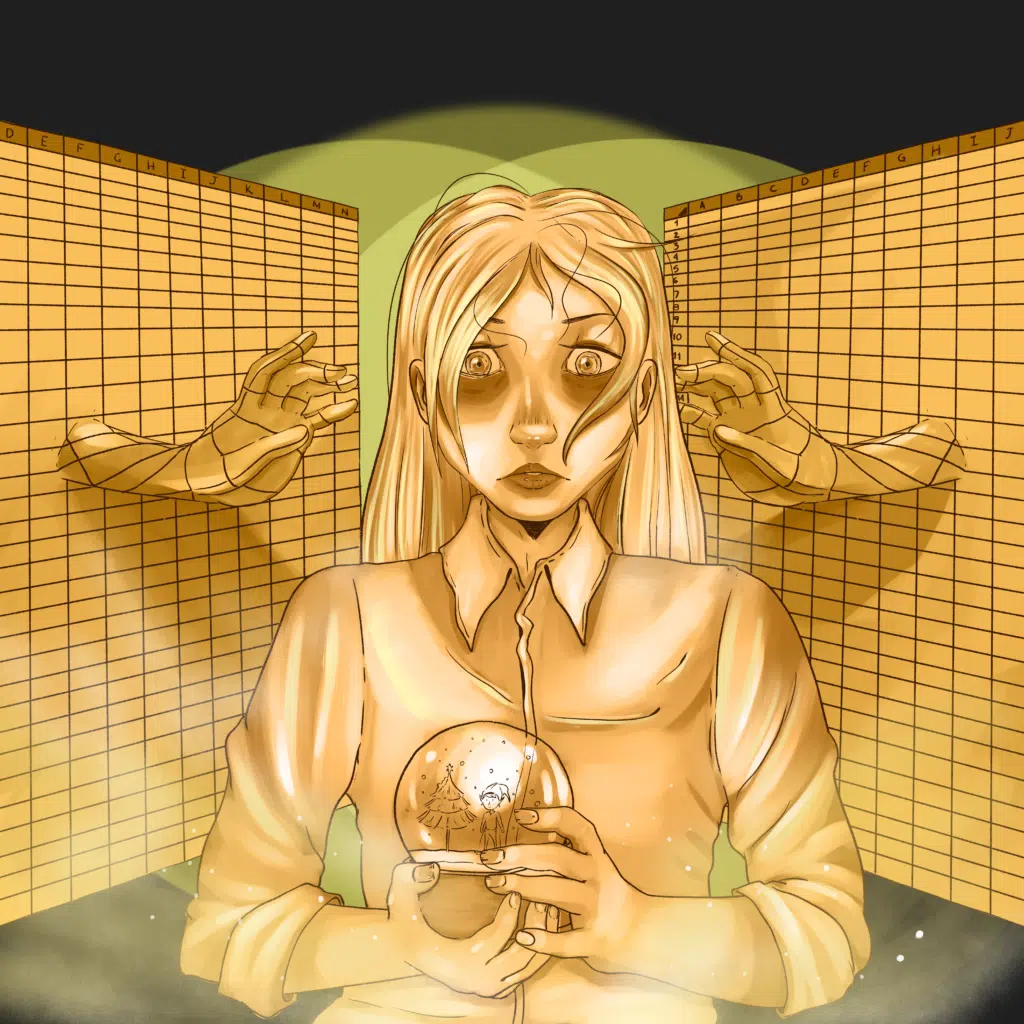

A presence extending beyond the monitor, steadily moving in closer. White, shimmering in the manner that a screen shimmers, which means a steady, uncomfortable sort of shimmer. Interwoven in the white were the familiar thin lines of what Sara had always supposed from her days of dabbling in graphic design: a hex value of #808080 or thereabouts, meaning a medium but pale-ish grey.

Even though Sara was keeping her eyes on her work, keeping her eyes straight ahead, she could see the way the white and the grey lines were moving beyond the borders of the monitor, crowding out her view of the door and the bookcase.

Also, the snow globe. The snow globe sat on the top shelf and contained a tiny elf wearing a green hat and red jacket, his little face tipped up in exuberant drowned wonder, tiny white pieces of plastic scattered around his ankles. The snow globe didn’t belong to Sara but was left by the person who had this office before; her name was Lucy (and, presumably, still is), but no one says her name out loud anymore; her name is only spoken in whispers.

Lucy was a well-meaning but terrible employee who wasn’t quite fired, exactly, but her position was eliminated, which happened soon after a company event during which she apparently got so drunk that she began dancing in the company auditorium to a Neil Diamond song, and singing on top of it all, swaying drunkenly in the center of the room, her dress falling off her shoulder. (Although it often appeared that things were falling off her shoulders because they were rounded, sloped, and small for her frame. Beneath her shoulders, the rest of her ballooned out softly; she had large breasts and even larger hips, and only wore clothes that puffed softly around her as she walked, which had the effect of making her appear perpetually blurry around the edges.)

Then she began to dance, tentatively at first and then—as she tossed back a shot or two, gradually picking up steam—graduating to kicks and pirouettes—it was remarkable, really, how gracefully she moved despite her bulky, out-of-proportion body. But she was wearing a pair of delicate black patent leather heels everyone agreed she didn’t look very stable walking in all evening, and she eventually tripped on a cord that the A/V guy hadn’t taped down correctly and went down, tumbling to the floor, where she lay for a moment or two before she started to cry. This story was strange, certainly, but it began to make more sense once it got out that Lucy confessed to Dolores in Contracts that she was hopelessly in love with someone who worked there, although she never said who it was.

Oh, everyone said, nodding when they heard. That explains it.

So, Sara leaves the snow globe with the little elf on the top shelf of the bookcase because… well, she doesn’t know why exactly, other than something in her feels a connection to Lucy. She never knew her, exactly, except to say hi when passing in the halls. But there’s also the matter of their shared office. Sometimes she gets the idea that she can sense Lucy’s presence, the tortured gloom of her thoughts.

But, of course, that’s ridiculous. Lucy isn’t a ghost, and she isn’t haunting anything. (And even if she were, what ghost would choose to haunt an office?)

Also, there was the time that Sara had to crawl under the desk to retrieve a mint and found a ripped fragment of paper with the words

I can’t, you know that, but I wish—

Sara stared at that paper for a good ten minutes or so until she carefully folded it up and tucked it in the back of her wallet. She doesn’t know if it was written by Lucy, but who else would have written it? She doesn’t understand why she keeps it, except that it seems proof that offices are full of mysteries.

And anyway, the reason she is thinking about mysteries, Lucy, and the strange things that happen in offices is that she is trying hard to ignore the fact that the spreadsheet people have surrounded her; they have begun to do what they always do, which is to take their long thin lines with hex value #808080 and use their shimmering blue-white hands—yes, they have hands; she can feel them, they are a little chilly, even, although maybe she imagines that part—to bind her in place, to keep her head, neck, shoulders, arms in place while she stares ahead, concentrating on her formulas.

She can’t allow herself to look away from what she’s working on, a single slip-up could mean transposing that error to multiple cells, something that would be easy to miss in the short-term but would be found eventually, and she would be blamed. They would whisper about her like they whispered about Lucy; that single mistake would lead everyone to the inescapable conclusion that she’s not the person she spent eight hours a day for years and years trying to convince everyone she is.

The next quarter arrived, as quarters always do, and business rose and fell the way it always does. Although during this particular quarter it probably wasn’t rising at the rate that senior management would prefer and it was falling somewhat more, which was illustrated in the literal sense in the charts on the large monitors in conference rooms. Executives stared at the charts with a new intensity.

Even Ed, the easygoing one, the one who was always jokingly saying that someday he was going to win the lottery and get sprung from this place, was no longer joking or smiling when Sara passed him in the hallway but rather clutching a paper coffee cup and staring down at his feet, moving down the hall as fast as he could. That same intensity was mirrored in the spreadsheet people, Sara could tell; out of the corner of her eye, she could see a trembling at their edges, a sort of vibration, as they pressed themselves all around her. They’d gotten more aggressive; that was clear; they pressed closer to her as she sat at her desk, a chill radiating off their cool shimmering bodies; they wrapped their grey lines around her tighter than they ever had in the past.

What was happening with the spreadsheet people was disturbing, but Sara didn’t have time to dwell on any of it, as she had other things to focus on. Work, obviously, but also other things, such as the looming shadows of the holidays. All that fa-la-la, etc.

It was a Thursday, and she was thinking about all of this while she worked on her spreadsheet, diligently (as always) copying and pasting formulas, values, columns. Today was the deadline; she had to email it out by five; people were already asking about it.

The spreadsheet people were there, of course. These days, they always were. They’d become increasingly bold, occasionally roaming around her office or sitting cross-legged on her desk, peering down at her while she worked. She’d started to be careful about always keeping her office door closed. (She was never sure if other people could see the spreadsheet people as well and wasn’t sure if she wanted to find out.) T

he spreadsheet she was working on was the same one she’d been working on since summer, and, over time, it had grown in a manner that was starting to seem out of control; there were now so many tabs that she had to scroll for what seemed like (but surely wasn’t) several minutes to see them all properly, and so many columns that often when she scrolled to the right to see all of them she had the fleeting impression she was lost in a cool dank forest somewhere, but with spreadsheet columns with alternating background colors for cells towering over her in place of trees.

It was while she was working on this, scrolling somewhere in the middle of tab seventeen, becoming so exasperated with a particularly tedious copy-and-paste task that she sighed out loud, that she noticed, out of the corner of her eye, that one of the spreadsheet people, who (for days? weeks?) had been sitting somewhat apart from the others over on the floor closer to the bookcase, swiveled its head to—apparently—look at her. However, it didn’t have eyes or any features to speak of, exactly, just thin grey lines that arced and dipped in the way you might imagine they would if they were tracing eye sockets, noses, lips on human faces.

This was startling enough that Sara stopped looking at the spreadsheet. Moved her hand away from the mouse.

The spreadsheet person turned away, its attention now seemingly focused on the snow globe on Sara’s bookshelf, the one with the drowned exuberant elf. It ran a pale hand over the glass while emitting a sound that sounded a little like a sigh (albeit a spreadsheet-y sort of sigh). That was when Sara saw how the spreadsheet person’s shoulders were slightly sloped and how heavy its chest was, almost as if it had—

Breasts.

Outside Sara’s office, the printer hummed distantly through the door. Somewhere, a phone trilled in a distant, watery sort of way. But she was only vaguely aware of these details.

So, yes—the first shocking thing was that the spreadsheet person was a woman. But, even more shocking was that Sara thought she recognized her. Not her face, of course, since that was only comprised of spreadsheet cells. But her body. The unmistakable heaviness of her chest area was visible by the way the grey lines bulged. The heaviness of her hips. Also, the faint blurriness of her edges.

Sara swallowed, her throat dry.

“Lucy?”

The spreadsheet person’s head shot around. All the grey lines in its body straightened simultaneously as they were being tugged from above by a puppeteer.

Time slowed and curled in on itself like a long, languid comma.

Yes, Lucy had “moved on,” as they say, but not in the way everyone meant.

Obviously.

Lucy had been so eager to please, Sara remembered. So anxious to be recognized and accepted. Never quite sure how to make conversation, never sure how to fit in.

But the spreadsheet people had accepted her.

The spreadsheet people had taken her in.

Then, a thought so strange and terrifying that Sara stopped working. Pulled her hands away from her keyboard as if the keyboard were on fire.

It was clear, all right. What they were pulling her towards.

Long before she ever saw the spreadsheet people, she’d felt them. The way they steadily eroded her thoughts, the way they scrubbed them clean without her consent.

They wanted her to join them. In fact, they’d wanted that for years.

Living with this knowledge was hardly easy. After all, she still had a job to do, and that job mostly involved spreadsheets—lots of them.

Also, there were the spreadsheet people themselves. They were no longer curiosities but rather malevolent beings.

A Wednesday, just after one in the afternoon. Time had passed, but how much? Sara couldn’t be sure. Months, certainly. The weather outside had changed several times: wind, snow, rain, etc. She remembered that the flowers outside the office had bloomed for a while, but they’d now been gone for a while too, so maybe it had been a year or so. Honestly, though, it was hard to tell since, inside the office, everything was always more or less the same; everything was always trembling on the brink of disaster.

Sara was trying to concentrate. She had an error in one of her formulas that she was struggling to figure out, but no matter how much she stared at it, retyped it, even; copying and pasting it into a plain text program to analyze it for the wrong kind of brackets or extra spaces or a dollar sign where there should have been an ampersand or a semicolon where there should have been a colon, there was no help for it.

ERROR, the spreadsheet repeatedly told her, in red text to (viciously, she thought) underscore its point.

ERROR.

She stared at the screen, all the characters in her formula swimming together, nothing making any sense.

Behind her, she felt the hazy plasticky nothingness of a spreadsheet person’s hand stroking her hair. This sort of behavior was new. Gradually, they’d become bolder, testing their limits.

Sara took a deep breath, deciding to block them out. Stared straight ahead at the monitor, placing the cursor in the cell with the formula she needed to edit. Typed the symbol for equals, followed by “IF”—

Stared at the screen. A spark of an idea flickering inside her, trying to get her attention.

=IF(REFUSE*RESIST—

No, she thought, hitting the backspace button. That wasn’t quite right. Too direct. Also, maybe even a little cliché. The spreadsheet people were peripheral; she knew that. Sideways. Not direct at all.

Greater than. As a child, math had terrified her. But the concepts of greater than, less than had made sense. More sense, than, say, something like working with fractions or calculating percentages. Comforting, in a way.

=IF(I>ALLOFTHIS

Sara stared at the blinking cursor, finger poised over the RETURN key. No, ALLOFTHIS was too vague. Spreadsheets did not accept vagueness in any form. This variable was doomed to fail.

But, no matter; she could try again.

All around her, the spreadsheet people shifted positions.

Sara thought harder about variables as she opened another tab, preparing to get to work. But then her fingers paused over the keyboard, considering.

In most cases, one needs to define variables before using them.

However, in this particular case… did she? After all, the variables were all around her. The variables were imprinted onto the air, woven into the furniture, reflected on the chrome accents around the office, the glass windows in the conference rooms, the skylights. Also, when she spoke while she was at work, the variables poured out of her throat.

Sara turned this idea over and over in her mind. Then she began to type.

As she worked, the afternoon wore on, as afternoons do; the grey clouds outside the window sliding by, thickening, dissipating, the light shifting. Occasional hushed chatter floated by her closed door.

Sometime later, she stared at the formula in front of her.

=IF(I>(LONGDULLAFTERNOONS,POINTLESSMEETINGS,FLORESENTLIGHTING,SMALLTALKABOUTWEEKENDACTIVITIES, BULLETPOINTS,CONFERENCECALLS,CALENDARINVITES,TALKINGABOUTTRAFFIC,TALKINGABOUTTHEHOLIDAYSCHEDULE, STALECOFFEE,STALEDOUGHNUTS,CLOUDDOCUMENTS,CLOUDHOSTING,CLOUDSTUFF, UNUSEDPHONESSTILLSITTINGONDESKSFORNOAPPARENTREASON,MALWARE,EMPTYCUBICLES, EMAILSFROMHR,MEDICALPLANS,DENTALPLANS,INFINITELYCONTRACTING401(K)PLANS, CC:FIELD,BCC:FIELD,DISTROLISTS,TIMEZONES,PERPETUALLYCOLDWATERFROMTHEKITCHENFAUCET, THESOUNDOFVACUUMCLEANERSAT5PM,SAYINGHELLOINTHEHALLWAYTOTHESAMEPEOPLEFORNEARLYADECADE, ISOLATION,EMPTYMEANINGLESSGOALS,MORESMALLTALK,MONDAY,MONDAY,MONDAY,MONDAY (,“SPREADSHEETPEOPLEVANISH”,“SPREADSHEETPEOPLEREMAIN”)—

The cursor blinked. The spreadsheet people—well, she could tell they were waiting, somehow. Not that they were holding their breath—because they were made of nothing but spreadsheets, they couldn’t breathe—but she sensed that they all contracted slightly, vertical and horizontal lines tracing paths that went simultaneously concave.

Hit the return key.

The first thing she was aware of was that the room was a fraction dimmer. Not by much, but a little. Sara sat there momentarily, not daring to look to the right or the left. Not daring to look at anything other than her monitor. But then, at last, she did, allowing her gaze to shift just beyond the edges of her monitors and then, finally, to take in the rest of the room.

All the spreadsheet people were gone.

But were they completely gone? Well, that was up for debate. In the months and years ahead, there were times Sara thought she could feel them trembling angrily from the confines of her computer monitor, desperate to get out. But she liked that if she were going to be honest. She liked the power she had over them. She had no sympathy for their plight. She wanted the spreadsheet people to suffer. Even Lucy; long ago, Sara lost any sympathy she’d once felt for her. After all, she’d had a choice. Hadn’t she?

Yes, Sara liked thinking of the spreadsheet people staying trapped forever and ever in their cold white land. She’d never thought of herself as someone who could feel that way about anything. Years ago, she used to think of herself as kind. But, apparently, she was a different person now.

Nominated for both the Pushcart Prize and Sundress Publications’ Best of the Net, Emily Zasada’s short stories have appeared in Your Impossible Voice, The Forge Literary Magazine, Straylight Literary Magazine, Qwerty Magazine, Menacing Hedge,Spectrum Literary Journal, and several others. Originally from the Baltimore area, she now lives in Northern Virginia.