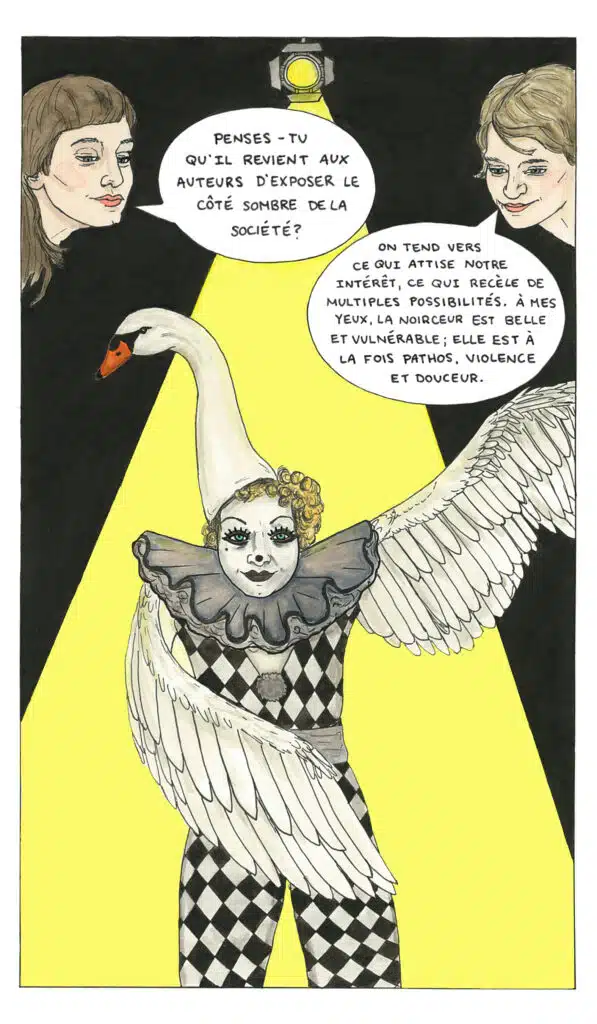

(Caption: ARIZONA: Do you think authors are responsible for exposing the dark side of society?

HEATHER: I don’t think any subject is dark to a writer. We are drawn to what excites us and is rich with possibility. I find darkness beautiful and vulnerable and full of pathos and violence and sweetness.)

By Jean Marc Ah-Sen,

Arizona O’Neill, a former bookseller and the mural artist at Librairie Drawn & Quarterly bookstore in Montreal, released her debut graphic novel with Publications Zinc in November 2022. Est-ce qu’un artiste peut être heureux? (Can an Artist Be Happy?) consists of illustrated conversations with twelve Quebecois artists exploring their personal definitions of happiness. Featuring musings by revered comic book artist Julie Doucet, indie pop musician Patrick Watson, street artist Miss Me, and O’Neill’s mother, the best-selling Canadian author Heather O’Neill, the younger O’Neill surveys the curative potential of discourse among colleagues, strangers, and friends. I corresponded with O’Neill to discuss the “ridiculous and sublime” instances of happiness, and the fantastical dimensions of her new release.

Jean Marc Ah-Sen: Where did the idea for the book come from, and why do you think experimentalism with form seems to be celebrated within comics more so than in other mediums?

Arizona O’Neill: I was asked to do a written interview with my mother, author Heather O’Neill, last year. Since I understood my mother’s imagination well, I thought it would be interesting to ask her about her lead characters and illustrate them with us in the room. This interview is included in the collection. It really sparked the creative possibilities of illustrating what’s going on in artists’ minds. The graphic novel form really allowed me to take interviews further into the fantastical realm.

Compared to other forms, the graphic novel is still a young medium. That is not to say that comics don’t have a rich history, but that the non-fiction graphic novel format is still fairly new. This is why we celebrate experimenting with the form because it is still growing and evolving, creating endless possibilities for the genre.

Jean Marc Ah-Sen: On top of showcasing your skills as a conversationalist, heureux features drawings that add a crucial visual component to the book. How did you go about deciding which locales and situations would contextualize your respondents’ lives?

Arizona O’Neill: The book is really a love letter to Quebec and its artists. A lot of time, I chose to draw us in my favourite Montreal spots. For example, I illustrated a conversation with Walter Scott in one of my favourite restaurants, Nouveau Palais. I would also ask the artists where they would like to be drawn in the city. The answer I had the most fun with was that of Klô Pelgag. She said she liked places that no longer existed, that are like invisible characters from another era in the neighbourhood. This allowed me to focus on landmarks I loved that were destroyed by lack of attention. One of the places I drew us in was the Robillard, which was the first cinema in Canada. The building burned to the ground in 2016 after having been abandoned for many years. Or the Super Sexe strip club whose giant seedy sign was mourned when the building caught fire.

And then other times, an artist’s answer would spark an image in my head that was more fantastical and in the realm of dreams. I really allowed the interviewees to guide my hand.

Jean Marc Ah-Sen: Your book engages with how the creative life colours an artist’s conception of happiness. Many of the responses exposed the belief that happiness is fleeting—do you think that this position is uniquely informed by the artistic temperament or the challenges of art making?

Arizona O’Neill: I think the elusive nature of happiness is something that torments everyone. But artists grapple with understanding emotions since they need to convey them in their work. As Paul Cézanne famously said, “A work of art which did not begin in emotion is not art.” So I thought they would all have had some reckoning with happiness. I don’t think that artists feel happiness or other emotions differently than others, but they might have more informed ideas about them. That’s the wonderful thing about artists: They take everything seriously, from a mouse on the counter to the meaning of life, and make art from their observations. So it was fun to see them try to capture the slippery nature of happiness.

Jean Marc Ah-Sen: You don’t really advance your own view of happiness in the book. Can you talk about your decision to foreground the respondents’ perspectives? Did you arrive at a sense of joy nonetheless at creating a polyphony of artistic viewpoints?

Arizona O’Neill: Surprisingly I feel very disconnected from the word ‘happiness’. I think it is too big of a word that society puts a lot of importance on. I preferred listening to multiple perspectives holding up fleeting, odd, ridiculous and sublime instances of it. Showing how happiness is part of the fabric of all experiences, even when banal, created this eclectic wild book, which pleased me. In my book, graphic novelist Mirion Malle, who often writes about depression, said “Happiness, for me, is the power to feel a range of emotions, not necessarily just joy.” And I liked that very much.