By Kevin Broccoli

She got sent out with a basket of pecan bread and a bad cough. The flu had whipped through and nearly killed Rebecca the same way it had four other little girls in town. This was going to be her first outing since she recovered, and her mother pulled the red bonnet tight on her head as though sunshine might end up bringing back Death to finish the job.

“Straight there,” her mother said, “I don’t want to find out you stopped to look at the horses at Friedman Ranch. This is a test errand. See if you can get there and back without collapsing. You do that, and we’ll talk about sending you back to school.”

Going back to school was Rebecca’s greatest desire. At age ten, she only had a year or so left before she’d be expected to drop all education and focus on helping out around the house so she could learn how to be a good wife one day. Truth was, she could already bake better bread than her mother and her fixation on making things clean meant she’d never been chastised for failing to do her chores.

“My Rebecca polishes plates like nobody else on earth,” her father bragged to anyone who would listen, “When I finally hand her over to her husband, he’s going to be thanking me for the rest of his life.”

If it had been up to her father, she’d have been out on the road before her fever had even lifted. Benjamin Hardy believed in Darwinism even if evolution was a sin. The weak withered in the desert sun, and the strong burned until they couldn’t feel it anymore. That was survival. That was how you persevered according to his version of Christ and salvation.

He and his wife never had another child after Rebecca due to a bad delivery that had almost cost mother and child their lives, and so he treated his daughter like a son, but only when it came to toughening her up. She was still expected to act like a young lady in dress and speech. It was her soul that her father wanted to masculinize. He wanted her to have the spirit of John.

Her mother’s only wish for her daughter was to stay alive. When Rebecca’s mother was nine, her younger sister had been bitten by a snake and died a bad death within a few minutes. She was raised by her father to understand that there was a Heaven and it was far better than earth, and she was raised by her mother to believe that any fool who goes rushing to Death won’t be meeting any God of Kindness when they perish.

All these thoughts were too much to instil in the mind of a girl Rebecca’s age, but nuance was required for life in and under the desert sun the same way water and shade was, and so she learned to hold what she could even as she was sweating in bed thinking soon she’d be finding out just how glorious the Great Glory was after all.

“Meesa’s expecting you,” her mother reminded her, using the nickname for her grandmother that she’d come up with as a baby and which persisted as some things relating to children often did, “You’ll spend the night there and return in the morning provided it’s not too hot. Otherwise, it’s two nights there and back the next day. Anything less than sweltering, though, and you’d better be home tomorrow. Wide eyes, Rebecca.”

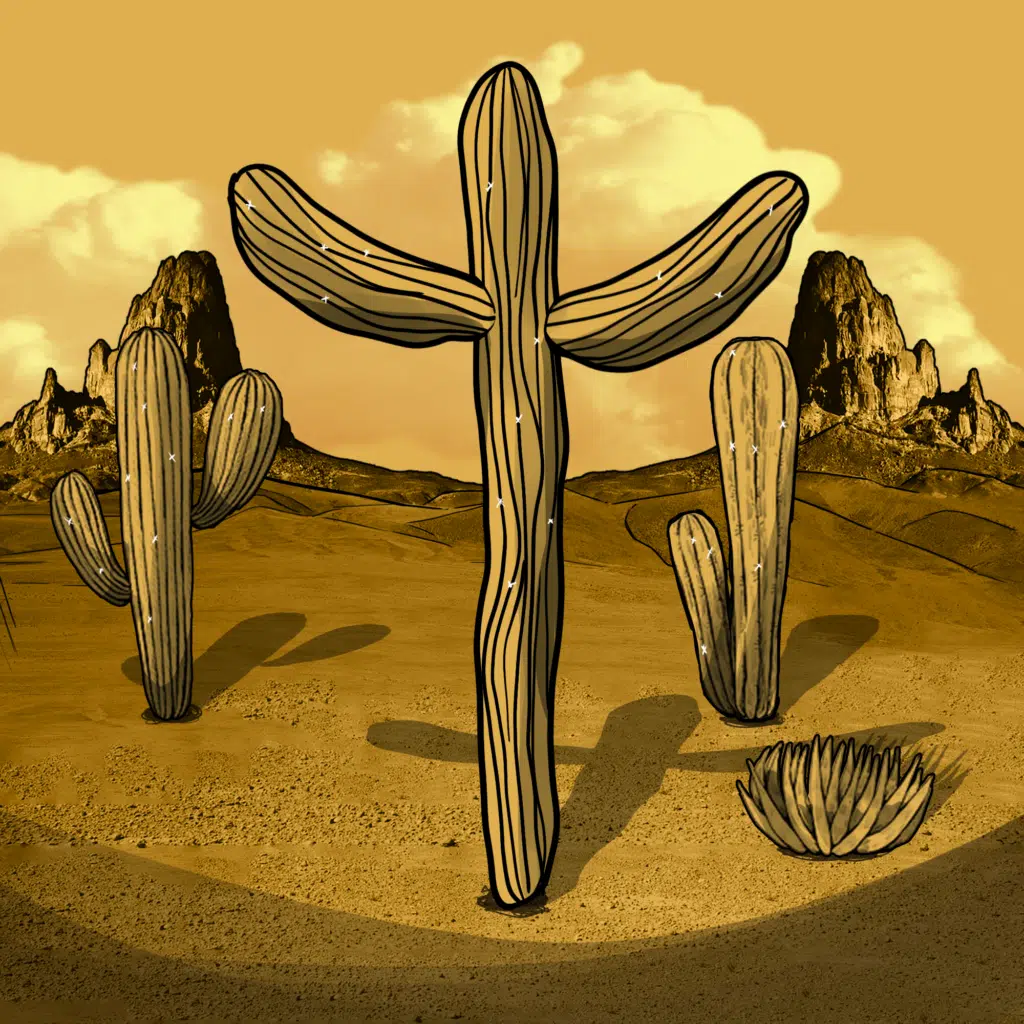

That was her send-off anytime she left the house, but today she noticed a quiver in her mother’s voice. She set out on foot and didn’t look behind her to see if her mother was watching her go. She had done this walk many times before, and all her landmarks were of the natural variety if you didn’t count Friedman’s Ranch. Rebecca had a habit of noticing flora and she was truly keen on cacti for its shapes and threat of pain. Despite her age, she could respect a living thing that developed in such a way strictly to protect itself even if it did keep admirers at bay. There was a cactus on the way to Meesa’s that reminded her of the cross, and she sincerely genuflected when passing by it on the narrow road.

The whistle came up behind her right ear before she knew what it was. The desert was like anyplace else when it came to sound, and she paid most of it no mind unless it was a coyote howl or a gunshot. Rebecca had only heard whistling a few times in her life. Her father would whistle on his way to the outhouse and back again. Rebecca had tried whistling once, but her mouth dried out too quickly.

“Where are you off to in a hurry,” a voice called from the dust.

She turned to see a man standing in the glare of the sun. The rays forced her to shield her eyes, but even then she could only capture so much of him. He had long black hair, and a beard that looked to go down almost to his chest. He was dressed like a preacher, but no preacher would ever let himself grow that unkempt. Rebecca knew this, because her father hosted traveling preachers all the time. They were cleanly men, even when they did stare at her mother a bit too long. This man wasn’t even holding a Bible.

“In a hurry to meet your maker?” asked the man, tempering it soon thereafter with a laugh, “Don’t mind me, young lady. I’m just not used to seeing anybody out here.”

Rebecca cleared her throat and introduced herself as Rebecca Hardy, daughter of Benjamin and Rose. Before she knew it, she was saying more than she should. She’d been raised to be discreet, but her sickness had knocked some senses around, and so while she knew she should wish the man a good day and hurry along, she mentioned her grandmother and a journey that would take a few hours thereby letting him know that nobody on either side of the road would be expecting her for quite some time.

“You shouldn’t tell a stranger all that,” the man said, seeming to read her thoughts, “Even a stranger of God.”

He tapped on his collar as though a costume proved anything. Rose was the one who called it that. Anytime one of those visiting holy men started going on, Rebecca’s mother would excuse the two of them claiming that her daughter needed a bath. As soon as the running water could drown out their voices, she’d confess to Rebecca that she found all those men to be nothing more than theatrical.

“They think if you look like something, that’s what you are,” she’d say, “But a costume just tells the world what they should be seeing. It doesn’t mean that’s what they’re going to get.”

The man began to walk alongside Rebecca explaining that he had business down the road, but much further than she was traveling. She considered offering him a piece of bread from her basket, but the food was not hers to be generous with as it had been made by Rose for her and her alone. When she coughed, the man asked her if she was feeling well, and she confessed that she was getting over an illness. She didn’t know whether it was a good idea or not to let this stranger know she was not at her full strength, however puny that might be compared to a grown man. Then again, a wild animal won’t attack a sick creature. No point in eating it after all. The question was–Is this man more tame than feral?

“I believe I should stop at Friedman’s Ranch,” Rebecca said, understanding all at once that after Friedman’s there’d be nothing on the road until her grandmother’s, and if the possible preacher had any ideas in mind he’d have no trouble executing them long before Meesa’s appeared in the distance, “Mr. Friedman is acquainted with my father, and he’d be cross with me if I didn’t say ‘Hello.’”

She could see the man absorb her strategy almost instantly. He knew what she was doing, but there was no way to protest without letting on that he had sinful intentions. Against her better judgment, she decided to push her luck and asked if he’d like to come with her. Perhaps Mr. Friedman would offer the man something to eat or drink since she hadn’t thought to allow him a taste of her mother’s bread.

“I suppose I can let you go,” the man said, seeming to choose his words carefully, words that implied a kind of permission, “Since all that is let go returns to us–in this life or the next.”

With that, he continued to walk on as she made the turn in the road up to the ranch only allowing herself to run once the man was out of sight.

Mrs. Friedman was feeding the chickens as Rebecca approached, and she smiled when saw her, having no idea that the young girl had felt so threatened only a moment ago.

“Why, Rebecca,” she said, “I had heard you were ill. I’m glad to see you’re feeling better. Heading to your grandmother’s? I could give you some cake to take with you, if you like?”

Rebecca remembered that the man with the collar knew exactly what her destination was, and she knew that Meesa wouldn’t be much of an obstacle if he was set on waiting for her there. She could go home and alert her mother and father, but if the wait proved to be too long or if he began to suspect that she’d assembled reinforcements, he might harm her grandmother out of frustration and then make his escape.

She could only find one solution for the moment.

“Mrs. Friedman, ma’am,” she said, attempting to make her next words sound as innocuous as possible, “May I borrow one of your guns?”

* * * * *

Rose got to the house first. When Walt Friedman showed up telling some story about how Rebecca had come by asking for a gun in case she encountered a coyote on her way to Meesa’s, her mother knew instantly that something was wrong. Friedman thought the story sounded suspicious, and his wife had said that the girl had seemed startled, but she loaned her the gun anyway, because she had chores to get to, and something about the girl’s demeanor begged Isadora Friedman not to ask too many questions. When Walt got home from town, she’d told him about it straight away, and he’d decided to ride to the Hardy house and convey the information just in case there was anything to it.

Some stories itch on you like a rash, and this one set her mother’s skin ablaze. Her father took the story for what it was. His daughter must have spotted a coyote and wanted some protection should it come upon her again–just as she said. He’d taught her how to shoot, and he was confident she could handle herself with just about any kind of gun. It was Rose who knew that her daughter wouldn’t veer off course and borrow someone else’s gun all on account of some desert wolf.

Despite her husband’s protestations, Rose saddled up their Percheron and rode as fast as she could down the same road her daughter had traveled, praying she wouldn’t see anything on the way that indicated some kind of trouble. The saguaro that marked certain miles along the way were casting shadows that looked as though they meant to grab at Rose’s horse. She’d never seen them that way before, but now everything appeared sinister to her. There was nothing friendly in this world now. Something had come looking for her daughter.

Meesa had a kutcha house that sat on a few acres of land past the spot where the dirt ran red for some reason nobody could explain. Rose dismounted the horse near the front fence and walked carefully up to the entryway. Her mother never believed in doors, because she wanted airflow and visitors. Benjamin’s pistol was strapped behind her back, and while she wasn’t as good a shot as her husband or her daughter, she could still take out a tin can sitting on a post at close distance if somebody dared her to do it.

The first step inside took you to the kitchen. It smelled of fried dough and palo verdes. Meesa would start cooking at dawn, and if Rebecca was coming for a visit, she wouldn’t stop cooking the entire time she was there. Sometimes it seemed as though her goal was to send the girl back twice as big as when she arrived. Rose put away her fondness for the aromas of the house she grew up in, and tried to concentrate. What was out of place? It didn’t take her eyes long to find the anomaly.

A man was sitting at the kitchen table with a bullet wound in the middle of his forehead. The shot had knocked him backwards instead of down. In front of him was a knife, but the blade was clean. Rose heard a sound behind her, and she nearly had the pistol out before she turned and saw who it was.

“About time you showed up,” Rose’s mother admonished her, holding a shovel in one hand, “Rebecca’s out back washing up. We should have this fool buried by lunch if we move fast. I hope you don’t think I’m the one who’s doing the digging.”

* * * * * * *

When the preacher showed up brandishing a knife, Meesa didn’t put up a fight. She did as he said and sat down at the table. He explained to her that they’d wait until her granddaughter showed up and then he and Rebecca would be leaving together, and if Meesa tried to stop him, he’d gut her right in front of the little girl with no qualms about it.

Meesa knew a man like this doesn’t leave anyone alive behind, and so she decided that when Rebecca arrived, she’d act as though she was going to give up the girl, and then throw herself onto the man. That would give her granddaughter a chance to escape, and a chance was better than nothing. Meesa would be killed, surely, but she’d had a long life, and she wasn’t about to go out like a coward.

As she sat, Meesa closed her eyes and tried to transform the world into manageable pieces that she could convert into energy for what might transpire now that evil had placed itself in her kitchen. She thought of her mother and how she’d feign weakness whenever it was called for only to snap like a wild dog as soon as someone put a hand on her. It was her mother that sprang to mind when she heard footsteps coming up the path past the fence. Meesa opened her eyes to see a smile slither onto the preacher’s face. He was still smiling when the shot rang out. Meesa barely jumped. There are lives that are built for surprises, and hers had been one of them. She looked at her granddaughter standing in the entryway holding a gun that was nearly as big as she was. The little girl was trembling a bit, but her hand was steady.

Meesa got up from the table and made her way to Rebecca. The gun was still aimed at the scoundrel even as a puff of smoke was rising off his forehead.

“It’s all right,” Meesa said, carefully taking the gun from the child, “Unless he’s the Devil himself, you won’t need to fire that again.”

* * * * * *

Rebecca rode home on the back of the horse. Rose had chosen not to speak to the girl until the preacher, or whoever he was, had been buried and a small lunch consumed. Meesa had said to let the girl stay for a few days and recover, but Rose wouldn’t hear of it. There was some kind of shock present, that was certain, but Rose wanted her daughter home with her, and they would take it from there.

When they passed the first saguaro, it occurred to Rose that now it didn’t look as though the cactus was trying to grab the horse, but that was just the way the shadows fell. Some cast themselves ahead of you, and some languished behind you. It all depended on which way you were coming from and where you were headed.

Rose wanted to tell the girl that no matter her actions, she would see the Heaven her father had promised. She wanted to impress upon her that bad men require bad actions, and those actions couldn’t imprint themselves upon you so long as you relinquished them from your mind the first chance you got.

There were all kinds of things she wanted to say, but the sun was hot and unforgiving regardless of what forgiveness was necessary. So they rode, and Rose told herself she’d speak to the girl at bedtime after lying to her husband and telling him that it was only a coyote after all. Just a desert dog that needed to be put down.

Kevin Broccoli is a writer from New England. His work has appeared in Molecule, Onyx, New Plains Review, Havik, Ou, and Ponder Review. He is the George Lila Award winner for Short Fiction and the author of “Combustion.”