By RICHSKI

I conducted my interview with John Ashfield as part of a university-led project to record recollections of the last remaining World War Two veterans. John told me that he had only shared this story with a single person, and it was not his wife. He feared that the revelations would make her uncomfortable and disrupt their intimacy. He insisted that our interview remain confidential while he and his wife were still alive. John passed away peacefully in 2015, about a year after our meeting, and his wife died in 2019.

* * *

You want to know what happened to me during the War? I never speak of it. I was trained to kill; that was regrettably necessary. But to kill efficiently you must be trained to hate; that is what I can’t abide, the hate that I felt, the need to make the enemy less than human. I never speak of it. What I will tell now mainly happened afterward. This too I have kept secret, not because of shame, but for other reasons entirely.

My brother had been a Navy flier, awarded a medal after Coral Sea and killed at Midway, so I was gung-ho to enlist. My two years of college and ROTC training gave me a leg up, and late ’44 found me commanding a platoon as part of MacArthur’s invasion of the Philippines. Things were especially rough in Corregidor —banzai charges and sudden ambushes from out of nowhere. A lot of our combat involved torching enemy troops holed up in underground bunkers. Sometimes the noise of the flamethrowers or exploding gasoline wasn’t loud enough to drown out the screams, and the smell of burning flesh was revolting. I only hated the enemy that much more for forcing me to do such inhuman things.

The summer of ’45 found me stationed in Guam, recuperating and getting ready for the invasion of the Japanese homeland. I had heard what went on in Okinawa, with resistance to the last man and mass suicide of the civilian population. I should have been terrified, but I guess my experience on Corregidor had left me numb, a zombie killing machine. When we heard about the nuking of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the emotional release left us all jubilant, and on V-J day we partied like they were doing back in Times Square.

I continued with McArthur as part of the occupation force, and in late September I was assigned to a team investigating the possible deaths of U.S. prisoners at Nagasaki. Hiroshima and Kokura had been the primary targets for the two A-bombs, and care had been taken to select sites with no POW camps. However, cloud cover had forced the second bomber to divert to Nagasaki. With fuel running low and clouds still an issue, they had released the “Fat Man” plutonium device and headed for home. We had reports that the Nagasaki Boiler Works, close to ground-zero, had housed a barracks for POW labor.

I could not believe the devastation when we arrived at the site. Some structures at the harbor-side were still standing, but where the bomb had detonated above the Urakami Valley there was nothing but rubble and dust for half a mile. The Boiler Works, just outside this zone, was a mass of twisted steel girders and not much else, but we discovered that the cellar of what proved to be the prisoners’ barracks was somewhat intact. When we excavated the area over the course of three days, we found a cache of metal boxes that contained personal effects of the prisoners. There were no remains to be recovered, but at least there would be something to provide closure for the families of these fallen heroes. We didn’t know much about radiation, but we did know to get the hell out of there ASAP. Fortunately, the dust had prompted us to all wear full-face respirators while we were digging, so we didn’t get much of that shit into our lungs.

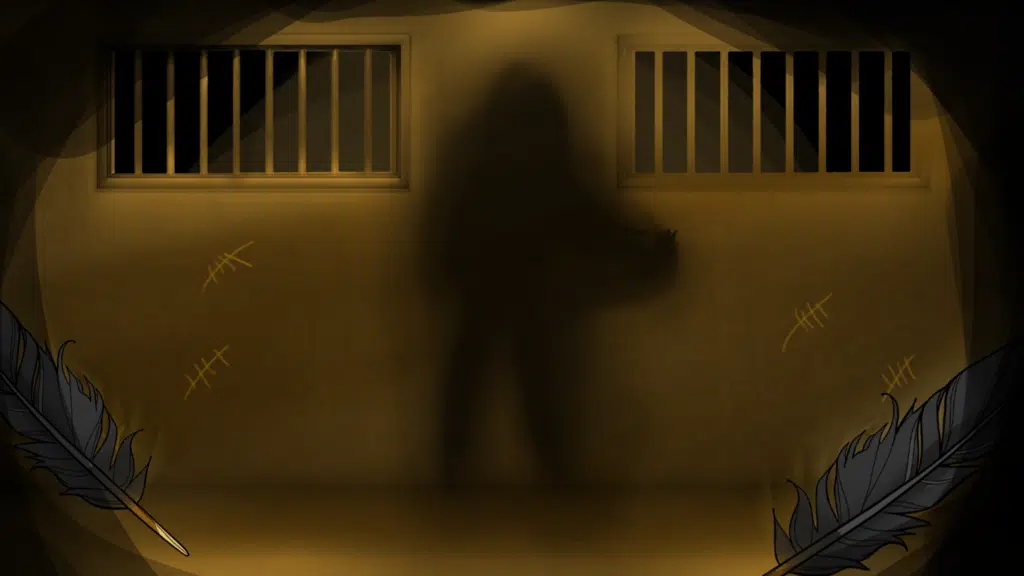

One image caught my attention as soon as we entered the grounds. The thick stone wall separating the barracks from the street had been bleached white by the heat of the blast. In the middle of the wall was the shadow of a man, with arm outstretched to the sky. (I subsequently learned that such death-shadows had been observed in both Hiroshima and Nagasaki.) It was easy to figure out what had happened. As it was being incinerated, the body of this hapless sap had blocked the tsunami of heat from reaching the wall, leaving his shadow permanently on the stone. I shuddered to think that this could have been one of the POWs…probably not, as they all would have been at work in the factory. I wondered at the outstretched arm—was he pointing towards the plane and falling bomb, or perhaps shielding his eyes from the initial flash? Was he waving to someone? We would never know, but somehow the gesture made this shadow on the wall into a real person. A Jap, yes, but someone not so much different from me.

On our last day there, just before we left, I grabbed a smoke and took a last look at this shadow. Something happened. When I first glanced up after lighting my cigarette, I saw not a shadow but a man, gaunt in a too large Japanese soldier’s uniform, black patch over one eye, scar across his face. He was smiling. The image only lasted a second or two. I blinked my eyes, and all I saw was the shadow.

This kind of mind trick had happened to me before, so I wasn’t really spooked. I remembered being on a camping trip when I was a teen, seeing a tree stump out of the corner of my eye as a crouching Indian. I knew even then that it wasn’t real—I’d just seen Drums Along the Mohawk with Henry Fonda. But I still spent a restless night worrying about every slight noise outside the tent.

One curious thing though; my imaginary soldier held an apple in his outstretched hand, as if he had just picked it. I checked the grounds near the wall and, sure enough, found the charred remains of a tree stump.

I forgot this incident fairly quickly as my responsibilities with the reconstruction effort rapidly increased. I was put in charge of food procurement and distribution for the entire Prefecture. I let go of my hatred and learned to admire and respect the character of the Japanese people—patient, diligent, humble, and kind. I became honorable Ashfield-san, and developed a real fondness for all the locals that I dealt with.

When I returned to the States, I pursued a B.S. in agriculture through the G.I. Bill, and eventually got a Ph.D. in Forestry. I had a rewarding career with a series of Environmental Organizations, mainly setting up Nature refuges. After seeing the war do so much damage to the ecology of the planet, I guess it was my way to make amends.

In 1995, shortly after I retired, I learned that my veterans’ group was organizing a trip to Japan for the fifty-year commemoration of the declaration of peace. With my wife’s encouragement, I signed up. She chose not to come along. (I think she sensed that I had some issues that I needed to work out on my own.) One of our first activities was a visit to the Nagasaki Peace Museum. There was a newly installed exhibit entitled Hitokage No Ishi—“Human Shadow Etched in Stone.” There, illuminated in a glass case, was the bleached wall that had confronted me fifty years before. The accompanying documentation included photos of the victims at the Boiler Works barracks, both POWs and guards. One of the Japanese soldiers was gaunt in a too large uniform, with a black eye-patch and facial scar—Shigeru Fujimoto.

I learned from the Museum that Shigeru’s sister, Sakura Kobayashi, had been a driving force for the installation of this exhibit. I managed to obtain her contact information, and had our tour guide compose a letter to her in Japanese seeking to arrange a visit, explaining that I had been part of the team that had investigated the Boiler Works site back in ’45, and had later coordinated food resource allocation in the Prefecture. Her phone call in response revealed that she was fluent in English, so I was able to journey to our rendezvous without the accompaniment of a translator.

I met the recently widowed Mrs. Kobayashi at her home in the quaint village of Hasami, near Sasebo. She seemed older than me, but her eyes were still bright and her smile charming. She was eager to tell me of her brother. Shigeru had been damaged both physically and mentally by his wartime experience in the Philippines. When he returned to Hasami to convalesce, she was shocked that the sweet young man she had known now suffered a paralysis of bitterness, raging against both the Americans and the Imperial army. But his love of nature had lifted the darkness of his soul, and he was able to return to light duty as a guard in Nagasaki. His last letter to his family had told of his joy at establishing a garden in the midst of the bustling industrialization of the city. He even expressed kindness towards the prisoners in his charge, and confessed to passing them fruits and vegetables, in violation of regulations.

I told her of my experience of seeing her brother’s image in the shadow on the wall. She gasped and cried, “Yes, I’ve seen it too, but I thought it was only in my mind.” She wept on my shoulder for quite a long while. We communicated without any words at all, and it felt as if we were touching each other’s souls. Afterwards we had tea, and she presented me with a beautifully lacquered box containing a tea set she had helped make at the Hasami Pottery Works. She shared family photos from the happy times before the War, and also told me of her own struggle to survive in its aftermath. I realized that my work on MacArthur’s reconstruction team had helped this marvelous woman to make it through the trials of the post-war years.

I visited the exhibit at the Peace Museum once more before returning to the States. When I reached the Hitokagi No Ishi, something seemed to click in my head, like time itself turning off. Shigeru appeared right there in the case, looking at me with kindness, his outstretched arm now open-palmed in a gesture of greeting and friendship. The moment quickly passed, but I retained in my heart the knowledge that he had set me on the path to healing and wholeness on that grim day in 1945. And with that awareness, I found that he had come alive within me.

When I returned to the States, Shigeru came with me, and he has been with me ever since. I see him often in the urban garden we’ve reclaimed from a vacant lot in the most blighted neighborhood of the city. During the summer and after school, children come by to help with the work and to distribute our produce to neighbors. Some have asked me about the Japanese man they sometimes see diligently cultivating and weeding, who disappears into the stand of bamboo at the edge of the garden plot whenever they approach. I tell them it’s just my shy friend Mister Shigeru.

I’ve maintained a correspondence with Sakura, filled with an easy brother-sister intimacy that I don’t think my wife would welcome or understand. Often my letters to her include phrases in Japanese, a language I never really learned to read or write. I sometimes wonder if it’s me or Shigeru who is doing the communicating. At this point, does it really matter?

All my friends from the War years are gone now, and I know that I will be passing on too, fairly soon I think. And when I do, I know that Shigeru will be crossing over with me—my other, my shadow, my brother.

AUTHOR’S NOTES

Richard Krepski (RICHSKI) is retired from a 30-year career as research scientist and educator. He currently resides in the twilight zone between scientific rationalism and poetic lunacy. His writing, including stories, poetry, and essays, often has a spiritual theme, and has appeared in several journals, including Oberon, Fickle Muses, Closed Eye Open, Braided Way, Bolts of Silk, Mad Scientist Journal, and Tiferet.

This is a work of fiction. I know of no historical record of POWs at Nagasaki or of a Nagasaki Boiler Works. There were twelve incarcerated American fliers killed at Hiroshima. Shigeaki Mori, who barely survived the blast as an eight-year-old, devoted himself to researching their story, informing the families, and establishing a memorial for them at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park. President Obama met and embraced Mori when he visited Hiroshima in 2016.

The phenomenon of nuclear shadows at Hiroshima and Nagasaki is well documented. An exhibit entitled Hitokage No Ishi (Human Shadow Etched in Stone), preserving the shadow on the steps of the Sumitomo Bank in Hiroshima, is on display at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.