By Leah Eichler,

I can’t recall exactly what inspired me, in the late 1990s, to send that fax (a fax!) to Simon Weisenthal’s office in Vienna and request an interview. Weisenthal was already 90 and not very active in the day-to-day operations of the Documentation Centre of the Association of Jewish Victims of the Nazi Regime, although his assistant assured me he still visited the office at least a half-day most days. All I know is that I felt a sense of urgency; the clock was ticking.

It wasn’t an easy interview to procure. For one, it was in Vienna and it was still the early days of the Internet. I needed to fax my intentions for the interview, then somehow get there. I had planned to visit my uncle in Prague and thought generally speaking I could make my way from there. Still, my contract with the Jerusalem Report was up, and I had yet to start working for Reuters. I had no real outlet for the interview, so I did something that didn’t come very naturally to me. I lied.

Memories of the interview came to me the other morning after Twitter informed me that a video of a protestor yelling an antisemitic slur against Justin Trudeau was going viral. The Simon Weisenthal Center made a statement condemning it. (Note to reader: The Documentation Centre, and the Simon Weisenthal Center, are two different things. The latter paid Weisenthal to use his name, although he endorsed their mission.)

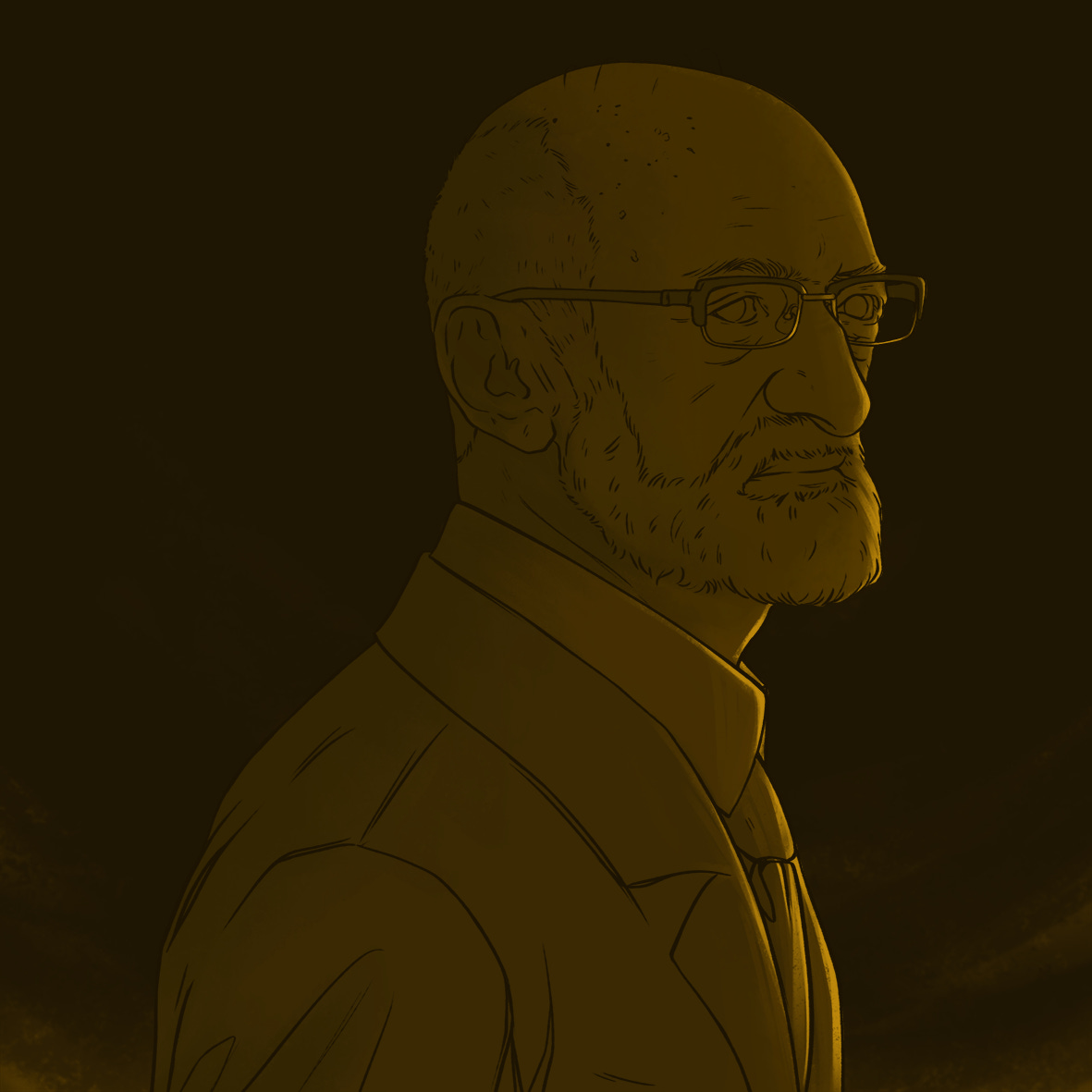

Still, just the mention of his name yesterday and I could see him sitting in a worn-out armchair, his small office overflowing with papers, when I reached out to shake his hand. In my entire career, I’ve never been speechless in an interview, but I struggled as I put my tape recorder on a nearby table. He looked a bit like my grandfather and I tried to reconcile that with the image of the demon slayer I had in my mind.

Like Weisenthal, who spent the latter part of his life looking for evidence to prosecute war criminals, I was also in some way looking for evidence. I grew up trying to glean snippets of my family’s history but the truth often seemed too hard to swallow. Sitting in front of me, Weisenthal was living proof that the history that shaped me was in fact real. On one hand, the truth petrified me, but on the other hand, there was Weisenthal. In my imagination, he was the ultimate badass protector.

As a child of the 1980s who spent lots of time in front of the television, I thought I knew something about heroes. While my brother preoccupied himself with pro wrestlers and Transformers, I looked for ones that fit my needs. Sure, there was Supergirl, and of course, I loved watching Jem, from Jem and the Holograms (truly outrageous!). But as the child and grandchild of Holocaust survivors, Jem didn’t really cut it.

Then I learnt about Nazi hunters, like Simon Weisenthal, and it didn’t matter that they didn’t actually hunt down Nazis and mete out justice themselves. In my imagination, that was going to happen anyway (cue The Boys from Brazil and Inglourious Basterds.).

In real life, Weisenthal was a quiet man; he spoke plainly in accented English, more like an academic or researcher than the gun-toting vigilante of my imagination. He believed in justice—but the old-fashioned way—and in records, and in exposing the truth. I had to reassess my internal understanding of superheroes.

In retrospect, the interview came at a time when I was struggling with my own identity. I started to shed my Orthodox upbringing when I was living in Israel and adopted the “living here makes you Jewish enough” mantra. But then I moved back to Toronto, and with no faith and no country to define me, I was left with the unsettling notion that I was not doing enough to justify my survival (I know how that sounds).

I believe in some way, I was looking to Weisenthal for guidance. When I left Vienna, I wasn’t confident that my mission was successful, but I threw myself into a career believing that even if I lacked faith, I had the truth.

Enter Henry Morgantaler. I had already worked for many years as a journalist when I convinced my bureau chief at the time to let me interview Morgantaler. It was, if I remember correctly, the 20th anniversary of Canada decriminalizing abortion. We really didn’t do anniversaries back then. In fact, I rarely remember us even writing about abortion. It was a controversial issue that popped up from time to time around major U.S. elections, but from what I remember, at least for Reuters, it was not considered overly newsworthy at the time (well, how things have changed!).

Morgantaler, like Weisenthal, survived a concentration camp. (Weisenthal was sent to the Lvov ghetto before being transferred to the Janowska concentration camp. Morgantaler, who was younger, was transferred with his family to a ghetto in Lodz, before being deported to Auschwitz and later, Dachau.)

Where Weisenthal focused his energy on bringing Nazis to justice, Morgantaler saw the plight of women suffering through back alley abortions, and often dying as a result, as a genocide of sorts — a crime he was intent to remedy.

I remember sitting in the waiting room with patients before the interview, and meeting him in what struck me as an ordinary doctor’s office. He spoke philosophically about the impact of bringing unwanted children into the world (increased crime, poverty, etc.) and the tragic loss of women’s lives in the many botched abortions he witnessed after the fact.

At the time, I didn’t agree with everything he said. I found his view on abortions to be rather cavalier, as in my mind he minimized the psychological impact on women, but I’d easily accept it today given the state of women’s rights. Ultimately, I found him inspiring; after all he’d been through, he was still up for the fight (and for returning to jail).

I don’t know that these two men ever met, but in my mind they live as one. I’ve interviewed countless people in the last 20 years but these two are the only ones I consistently mention. While both men were certainly flawed, they both defended intrinsic parts of my identity. I used to say I’m a woman first, and Jewish second, but I no longer think it’s pragmatic to pick. Our identities are complex, and I drew comfort that I could find, and speak with, two men who showed that something good can rise out of something terrible.

I think about Simon Wiesenthal and Henry Morgentaler a lot more lately. Both, I imagine, believed they were doing work that never would require repeating. If there is a next world, or Olam Habah in Judaism, I would love to know if they are hanging out in it together. Given the state of women’s rights and the rise of antisemitism, they may be tsk-tsking from heaven the state of our real worldly affairs. Or maybe, just maybe, they see someone ready to pick up their battles.

****

In other news, I was excited to be interviewed by Paul Zakrzewski in his podcast, The Book I had to Write. (Full disclosure, I’ve been working with Paul on a blended memoir and if this is something you are considering, I highly recommend him.) To listen to the podcast, you can find him here: The Book I Had to Write.

To listen to our interview, where I discuss the book I had to write, click on one of the streaming services below:

Apple: http://apple.co/3Dk2keg

Spotify: https://bit.ly/3XYZAfL

Yours in reading and writing,

Leah Eichler