By Patricia Crisafulli

A profusion of tiger lilies blossomed where the gravel driveway met the pitted blacktop of the country road. Pulling in slowly, Gabriela admired the red geraniums and yellow chrysanthemums that ringed the front of the small stone house with black shutters and wondered if these were the flowers Lucinda had wanted them to see. Taking in the bowling ball-sized stones that made up the outer walls, Gabriela tried to guess the age of the place. A hundred years? A hundred and fifty?

In the back, where the driveway widened into an apron in front of a small barn, Gabriela hit the brakes. Never had she seen anything like it. Multiple gardens stretched in all directions, each crisscrossed with flagstone paths. Some bore the full sun; others sheltered in the shade of four old maple trees. Before Gabriela could shut off the engine and unfasten her seatbelt, Agnese had opened the passenger door and pushed herself to her feet. Gabriela caught up with her mother at the side of a large vegetable patch.

“Zucchine, carote, pomodori,” Agnese exclaimed. “Just like in Italy.”

“I take it anyone who cultivates plants like an Italian can’t be all bad, eh?” Gabriela gave her a wry smile.

“Gardens, they don’t lie. To grow good things, you have to be—” Agnese muttered a couple of words in Italian. “Like Mother Nature.” Bending slowly, Agnese touched broad dark green leaves growing from a reddish stalk. “This one I know, but not the name.”

“Swiss chard,” Lucinda said behind them.

“You give me some?” Agnese asked.

Lucinda retrieved a pair of garden shears from a bucket of neatly arranged tools and cut a half dozen stalks. “Cook it tonight if you can, leaves and stalks both.”

Gabriela accepted the bouquet of Swiss chard and put it in her car, wondering how it would go with leftover eggplant Parmesan. Returning to the gardens, she followed one of the paths toward an herb patch. She recognized rosemary: spiky like an evergreen, growing in the bright sun and the reflected warmth of a flagstone step.

Lucinda walked up beside her, mumbled something to the rosemary plant, and snipped off a short branch with garden shears.

“Good for muscle pains, circulation—and commanding respect. Plus, it’s nature’s aromatherapy.”

Gabriela held the sprig to her nose with one hand and pointed to a bluish-green plant with the other. “Lavender?”

Lucinda nodded, then gestured toward what looked like a miniature conifer. “And that one is juniper. The berries are good for all sorts of things—arthritis, diabetes, stomach issues.”

Following Lucinda through the sun-soaked herb garden, Gabriela let the litany of names wash over her: yarrow, meadowsweet, chamomile, coneflower, feverfew, catnip, anise, a bay tree, spearmint, and, on the diagonal far away from its cousin, peppermint.

“Can’t let those get too close, they’ll hybridize,” Lucinda explained. “And over there by the driveway is lemon balm—also in the mint family. Loves the sun, hates good soil.”

By the small barn converted into a garage, something grew against a high fence—as big as a shrub but with delicate branches and feathery pointed leaves. “Artemisia vulgaris,” Lucinda announced, “better known as mugwort.”

Gabriela shivered a little at the name, though she didn’t know why.

“A staple in Chinese and Native American medicines,” Lucinda continued. “The Greeks used it. So did Roman soldiers, who lined their sandals with the leaves to keep their feet from getting tired on long marches. Regulates digestion and women’s cycles, heals bruising, and promotes lucid dreams.”

Gabriela looked around to see where her mother had wandered and found her bending down, fondling a plant’s fan-shaped leaves with scalloped edges.

“That’s lady’s mantel,” Lucinda called over to Agnese. “But it doesn’t like to be touched. Most plants don’t. It bruises them.”

“Scusa,” Agnese said, and Gabriela wondered if her mother apologized to Lucinda or the plant.

As they walked along the serpentine paths, Gabriela became aware of how much time must have passed, far longer than the twenty minutes she’d planned to spend there, but the garden held her captive. Every finely shaped leaf or wide frond, delicate blossom or showy flower begged a second glance, a closer look. Each moment offered another sweet fragrance or heady aroma.

Beyond the herb garden, ceramic pots spilled cascades of yellow pansies, red snapdragons, and purple petunias. Insects buzzed everywhere, more than Gabriela had seen in years. “Do you keep bees?” she asked.

“I like to think they keep me,” Lucinda replied. “They work in my garden as much as I do.”

“And they never sting you, right?” Agnese said, coming up behind them.

“Never,” agreed Lucinda.

Gabriela noticed her mother chewing on something and peered closer to see. Parsley. She waited for what Lucinda would say, but she didn’t seem to react to Agnese grazing through the kitchen herbs, or perhaps that’s why they had been planted.

The other half of the backyard was cast in the shade of four old maples planted in a circle. Below them spread a sea of plants bearing wide leaves with multiple points. “Goldenseal,” Lucinda said. “Many medicinal uses, but—” She snapped her head in the other direction, and Gabriela followed her gaze.

Agnese traipsed across the shadowy ground toward a patch of plants on the far side. Lucinda’s eyebrows pinched together. “Don’t taste anything over there.”

Lucinda walked quickly toward Agnese, and Gabriela trailed close behind. A short border fenced a small round garden where three plants grew together. Gabriela waited for the recitation of names, but Lucinda said nothing.

“This one, with the berries,” Agnese said, pointing. “I see it before.”

“Atropa belladonna,” Lucinda replied, “otherwise known as deadly nightshade.”

At the name, Gabriela curled her lip reflexively. “What are the other ones?”

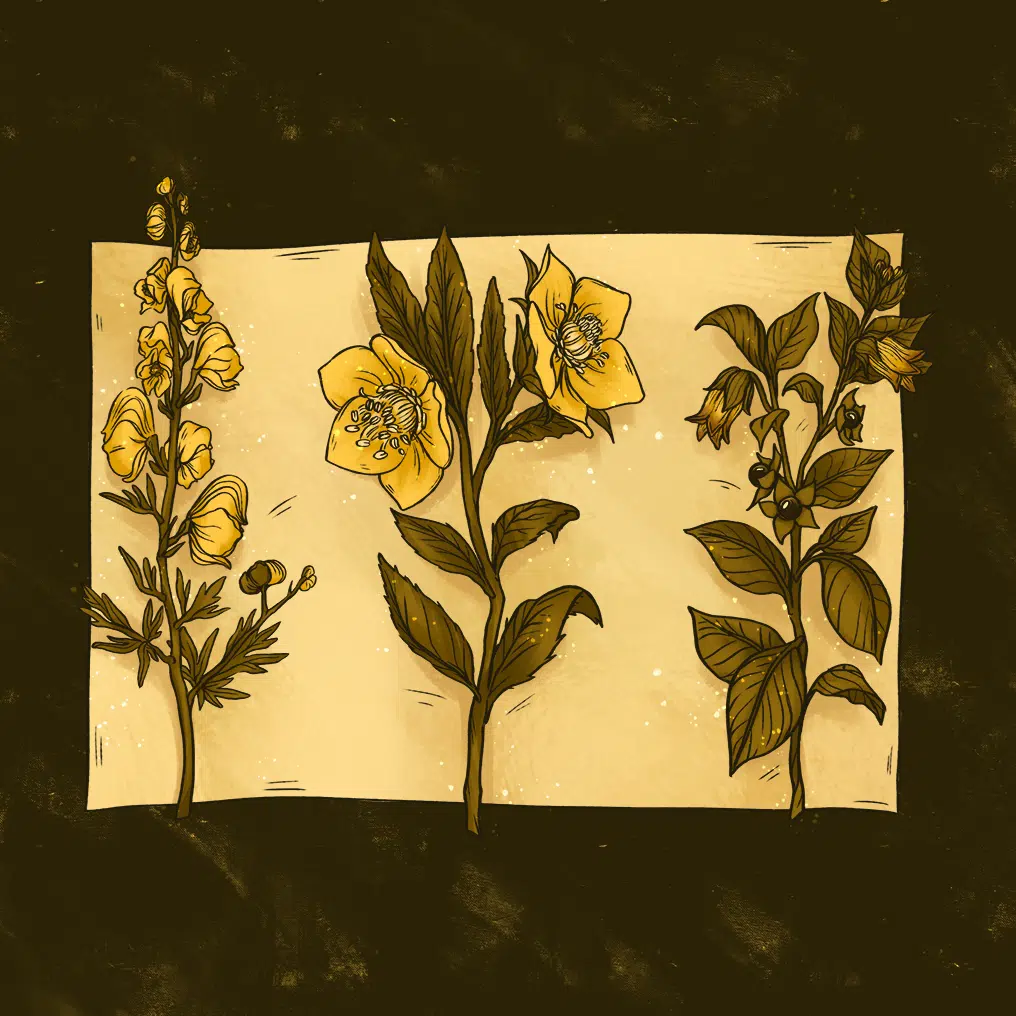

Lucinda paused. “Hellebore and monkshood.”

The shortened answers contrasted with the long explanations Lucinda had given for all the other herbs and flowers. Here volumes seemed to be left unsaid.

“I take it they’re poisonous,” Gabriela ventured.

Lucinda hitched up one side of her mouth into a crooked smile. “Almost anything can be toxic in the wrong dose. Let’s just say these plants are for a different kind of medicine.” She extended her hand toward the house. “Shall we have tea?”

***

The screen door yawned open on a long spring, then snapped shut behind them. Wooden shelves along one wall of the sunporch held mason jars where plant cuttings dangled long strands of roots into blue-tinted water. In the corner rested a huge orange tabby, his sides rising and falling with his breathing.

“Corky,” Lucinda said, and the cat raised his head. “I found him outside one fall day—wet and hungry. I opened the door, and in he walked. That was that.”

“Lucky cat,” Gabriela said. “And smart.”

“You sleep all day? Or you catch mice?” Agnese asked. Corky blinked, then proceeded to give his front paws a tongue bath.

They followed Lucinda into the kitchen where a steady breeze blew through the open window over the sink. The fixtures and countertop were old but immaculate. Gabriela detected no trace of cooking odors, only the sweet scent of herbs and flowers. Peach-colored paint covered the walls, and brightly printed curtains framed the windows. “What a lovely room,” she said.

“It’s old, like me. I’ve been here since I got married—fifty years ago. I’ll be seventy-two in December.”

The number shocked Gabriela, who would have guessed Lucinda to be closer to sixty.

“My husband died twenty years ago. My daughter, Trudy, lives in Maine.”

Agnese made a soft grunt. “Twenty years is a long time. Me, I be seventy-seven in January. But my Vincent, he died only four years ago.”

While her mother and Lucinda talked, Gabriela glanced at her phone and scrolled through several text messages—none of them urgent. She’d check the voicemails in a moment.

“All those plants—just for you?” Agnese pointed toward the sunporch and the gardens beyond.

Lucinda spread her arms wide. “I believe in abundance. When I have extra, I share. But I also receive in return. People bring me a dozen eggs from their backyard chickens or loaves of homemade bread. Pies, preserves, potatoes, apples—occasionally, a nice salmon fillet.”

Gabriela groaned with regret. “I’m afraid we’ve come empty-handed.”

Lucinda turned on the burner under a teakettle on the stove. “I brewed this while we were out in the garden. It should be just about ready.” She sat down at the table. “I am hoping you will do something for me. I’d like you to tell me what happened at the chasm.”

Agnese swatted Gabriela on the wrist. “Si! You never say a word to me.”

Gabriela picked up the honey dipper and held it an inch above the pot, watching the amber liquid slide down the grooves of the stick.

“There’s not much more to say. Daniel and I were hiking when we came across two people. The man was very sick—he was having a seizure. The woman looked like she was dead. She must have been unconscious.”

Lucinda poured their tea, drizzled honey into each cup, and slid one toward Gabriela. “Why did you think she was dead?”

“No pulse. Her body was cold.”

“Evidence of vomiting?” Lucinda asked.

“Yes, both of them.” Gabriela took a sip of the tea, which tasted sweet and not just from the honey. She sniffed the steam and detected anise.

“Sfortuna!” Agnese crossed herself.

“Poisoned—that’s my guess,” Lucinda said. “Could be any number of things. Belladonna would do it if they ate enough berries.”

“Like in your garden?” Gabriela asked.

“It grows all over the place—a common garden escape. Goes feral. Creeps out of its confines and spreads. But someone has to plant it first.”

Gabriela remembered the tiny garden with the three mysterious plants, sequestered themselves, and recalled their names again: monkshood, hellebore, and belladonna. She’d google them later.

“Well, whatever happened to those people, they got sick but didn’t die—fortunately. They left the beach, and they never showed up at any of the hospitals for treatment.”

Lucinda placed her palms flat against the table. “There’s something funny going on at the chasm. My dear friend Parnella lives out that way. She was coming home late one night—must have been after ten. She saw three black pickup trucks tearing down the road, one after the other.”

Pickup trucks roamed every country road, Gabriela thought, and three in a row meant nothing more than people heading to some honky-tonk bar.

Lucinda pursed her lips. “Parnella says that sometimes at night you can see lights up on the ridge around Still Waters. Not from houses or camps—out in the woods. One time she heard a humming so loud, she thought an earthquake was coming.”

“Perhaps it’s the state doing some work up there?” Gabriela suggested.

“At night?” Lucinda’s forehead furrowed. “You can’t find a game warden during the day because of budget cuts. I can’t imagine anybody from the state doing something up there at night. Then you come across two dead people who rise up like Lazarus and paddle their canoe away.”

No one spoke for nearly a minute. Gabriela’s mind raced right back to the scene at Still Waters Lake and her absolute certainty of what she’d witnessed: the woman dead, the man dying. But she had to have been mistaken. Their pulses had slowed, not stopped. They’d been ill, not dead, and somehow recovered. There could be no other explanation, she repeated to herself.

As they left the house and walked toward the car, Gabriela sidestepped a tall plant with blue starburst blossoms that bobbed at the edge of the path. As she passed, a half dozen bees took flight and danced a figure eight above her head.

She felt the strength of Lucinda’s grip as the older woman pulled her forward. “You’re drawn to these flowers. Or rather, they’re drawn to you. Close your eyes and quiet your mind.”

Gabriela set down her purse and a bag of tea Lucinda had given her. Stretching out her fingertips, she felt a tingle—or at least she thought she did. “I’m not very good at this. I can’t even do yoga.”

“Open your palms toward the flowers. Tell them in your mind that you mean no harm,” Lucinda instructed. “Ask if you can approach.”

Gabriela felt foolish, talking to flowers, but she overheard her mother making a request in Italian. “Bei fiori . . .”

“Now, cup the blossoms the way you would a child’s face,” Lucinda continued. “What do you sense?”

Gabriela thought of a dozen things, from needing to get back to work to the realization that she hadn’t checked the voicemails.

“Not your thoughts—your feelings.”

In a fleeting moment of mental quiet, something came to Gabriela, but she dismissed it as nothing more than the power of suggestion. In its wake, she could still name it: resolve, bravery. Before she said those words, her mother spoke aloud, “Courage.”

Gabriela gasped. “Yes, I thought the same thing.”

Lucinda’s face crinkled pleasantly. “As if you were on a mission?”

Gabriela hesitated, not wanting to retrofit whatever she had felt into her mother’s word or Lucinda’s suggestion. Yet both matched what she had experienced, even if only for a few seconds. “Something like that.” She picked up her things from the ground.

“Some people call it starflower, but I prefer its less picturesque name—borage,” Lucinda said. “It reminds me of an ancient proverb: ‘I, borage, bring always courage.’”

Gabriela scanned the backyard bounty of flowers, vegetables, and herbs. “Your gardens are amazing, but your knowledge is the most impressive of all. Do you consider yourself an herbalist?”

“That’s one name for it,” Lucinda replied.

A question sent out a tendril from her brain to her tongue, and Gabriela couldn’t keep from asking it. “What’s the other name?”

Lucinda’s dark eyes held hers for a half minute, unblinking. “I’m what they call a green witch, though most people drop the ‘green’ part.”

“Oh—” Gabriela began.

Lucinda angled her head to the side. “I just know plants and they know me. I can feel their properties, for healing and for harm.” She extended her hand toward a pot of multicolored snapdragons, close but not touching them. “These sweet ladies have a mild energy, but they’re good for protection. That’s why I plant them here. If someone is coming to my home to fool me, I want to stop that intention in its tracks.”

“You think somebody tries to hurt you?” Agnese asked.

“Not directly. But sometimes—” Lucinda shook herself in a little shiver.

Gabriela linked arms with Agnese to keep her mother moving down the path toward the car. As they walked slowly, she heard the rasp between her mother’s breaths and felt the bony press of her ribs. This time, Agnese accepted help getting into the passenger seat, a sure sign, Gabriela knew, that the outing had tired her mother.

Gabriela checked her phone, scrolled through the texts again, and listened to the voicemails. The first two came from Daniel, asking and then urging her to call him back. The other two, from a number she didn’t recognize, had been left by State Trooper Douglas Morrison, who stated that the body of a man had washed up on the opposite side of Still Waters Lake. The corpse matched the description of the man they’d found on the beach.

Sitting in her car, behind the steering wheel, Gabriela slowly detached from her surroundings. Her mother’s voice echoed at the opposite end of a long tunnel that dimmed her peripheral vision. The buzzing in her ears amplified into a siren shriek, and she slipped into someplace dark and distant.

Patricia Crisafulli is a New York Times bestselling author and an award-winning fiction writer. She is the author of the Ohnita Harbor Mystery Series, which launched in 2022 with The Secrets of Ohnita Harbor, and follows the misadventures of Gabriela Domenici, a librarian whose insatiable curiosity gets her into all sorts of danger. The Green Witch’s Garden is excerpted from her latest book, The Secrets of Still Waters Chasm. Follow her on Instagram https://www.instagram.com/triciacrisafulli/