By Sean Nishi

It can get exhausting. The school kids. The team building groups. The seminarians. Especially the seminarians. Today we have a group of skeptical Catholics come in. “What foul God would permit these defects?” says one priest-in-training. “Or rather,” says another one, “how can our faith match the fortitude of these individuals?” The seminarians have this long conversation after that, a chicken-or-the-egg-type of thing, until finally they ask me how I manage with my disability.

So I say what I always say. Which is, through the thoughtful contributions of guests such as yourselves.

To which a seminarian says: What is this, some kind of racket?

And another one adds: Not with our stipends, you don’t.

And after leaving Mangan, my supervisor, has me watch the training video again. It’s this animated thing from the seventies called You Make Yourself Amazing. It’s about this ugly tomato named Jeffrey who has lumps and dark splotches on his skin. Nobody at the market wants to buy Jeffrey. Eventually Jeffrey learns to see himself as broken, but not totally useless, and embarks on a new career path as compost.

“Go home and renew your daily affirmations,” says Mangan.

Which is: I am eternal sunlight. I am a loving breeze. I now choose to release all jealousy, pain, and anger.

On the way out I pass by Sam’s booth. Sam’s disability is a huge purple birthmark on the her face. It looks like dried-up raisin skin.

“Make way for the Human Butthole,” says Sam.

She’s probably the closest thing to a friend here.

***

Next morning the first guest of the day shows up.

It’s Mrs. Harper. She’s almost ninety and widowed with a pension plan from her late husband. She comes here once a week to remind herself that there are people worse off than grieving widows. Per usual she comes to my booth first to play with my stomach.

“Oh Daniel,” says Mrs. Harper. “How’s your tummy feel today?”

“Better now that you’re here,” I say.

Shyly she slips her hand through the plastic protection barrier where my belly button should be. My disability was being born with a fist-sized hole in my stomach. Without the plastic protection barrier my food would just spill out. Mrs. Harper knows to be gentle. It’s not comfortable, but it doesn’t hurt either. Plus she always tips well afterwards.

“My Edmond always felt for you Disabled,” says Mrs. Harper.

“He was an amazing man,” I say.

“We voted against the Genetic Desirability Act,” she says. “A sad state of the world we live in.”

“It’s alright,” I say. “We make it thanks to angels like you.”

Mrs. Harper blushes. She slips a twenty inside my hole.

“I hope to one day see you outside this establishment,” she says.

“Aw, you know the rules,” I say. Which is: No fraternizing with guests outside of the workplace.

She gives me a nice rub on the cheek as she goes to see the rest of the booths. But we all know I’m the only one she gives extra attention to. Across from me Sam rolls her eyes.

“Brown-noser,” she says.

***

Lunches I’m permitted fifteen minutes outside in Designated Areas.

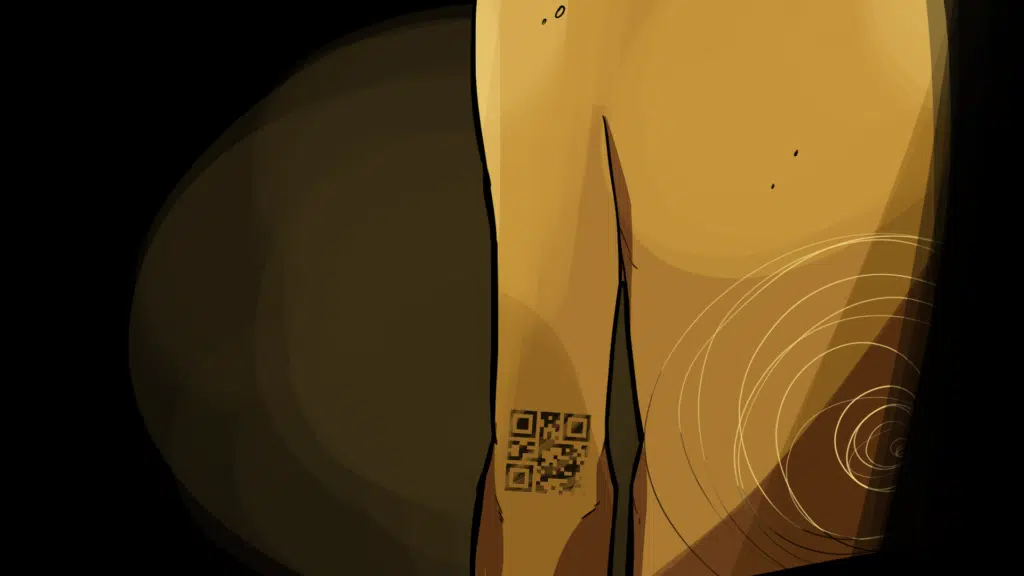

My favorite is the bird park. This is where the endangered species, the ones who can’t procreate anymore, go to live out the rest of their days together. I sit on a park bench across from the farmer’s market. In the old days I could shop with the rest of them. A time before QR codes on our elbows that give away who we are. Sometimes the vendors forget to check, but the penalty for shopping in an Abled Zone is pretty hefty. No. For me it’s the Disabled commissary with moldy sandwich bread.

On my way back I pass by the Abled-Now! clinic. For thirty-thousand dollars a doctor can sew up my hole permanently. But good luck ever saving that kind of cash. Not unless Mrs. Harper leaves me something in her will. Which is always a possibility. But I’m not banking on it.

***

When I get back Mangan is chewing me out for being late. I ask what the big rush is. But then I remember: It’s Children’s Education Day.

They swarm in on yellow short buses. Their teachers carry a spray that’s supposed to deescalate aggression. We regale the kids with tales about growing up in orphanages for the Disabled, where there were six heads to a pillow. Gollum talks about the day his basketball dreams were shattered because he doesn’t have any vertebrae in his back. Jerome recites poetry about the love of his life who left him when she saw his webbed fingers. Chrissy shows the scars on her arms from when she tried to remove her scales, until she finally accepted her role as the Snake Lady of Sioux Falls. When it’s my turn I do this trick with my stomach where I put a fake gerbil in the hole and then dare one of the kids to pull it out. I used to use a live gerbil, but I started to feel sorry for the little guys.

Then the kids start chanting: “Human Butthole. Human Butthole.”

Of course it’s Sam egging them on. I would yell at her but we’re not allowed to argue in front of guests. We’re supposed to be happy and humble, grateful for the opportunity to entertain the Abled such as themselves. So I smile and keep my mouth shut. Then a kid shoves half a PB&J inside my stomach, and the rest of the class moves on.

***

At home I shower and clean the peanut butter out of me. I catch a glimpse of myself in the mirror, and for a second I think I look pretty okay, cute even. But the damn hole. It really does look anal. I used to think when I grew up it would go away on its own. I used to think that Roslyn Abruzzi from freshmen P.E. would want to marry me. I used to think one day we would live in a fine brick house and thank God everyday that I wasn’t a Disabled anymore.

I used to dream a lot.

The next morning I get off the bus at work a few minutes late. I expect Mangan to yell at me. He likes to remind me that there’s a whole line of Disableds who would kill for my position. When I show up the receptionist Tiffany directs me to Mangan’s office. It’s cramped and windowless and smells like bug spray. Behind Mangan’s desk are all his baseball trophies. This business isn’t his. It’s a franchise that he bought after a knee injury crushed any dreams of hitting the majors, minors, any league really. Next to Mangan is a guy in a suit with thinning hair who says he’s a lawyer.

“Sit down,” says Mangan.

I expect him to have me clear out my employee locker, hand back the employee padlock, and get the hell out of here. But instead the lawyer hands me a pile of documents.

“Mrs. Harper passed away last night,” he says.

“Fell down her own set of stairs,” says Mangan.

“And in lieu of any living relatives, she named you her sole beneficiary.”

The lawyer flips through the documents to a paragraph in yellow highlighter. He points to the sum amount. I almost pass out when I read it. It’s enough for the surgery, with some leftover to take a little trip somewhere. Morocco, maybe.

“Available immediately,” says the lawyer.

At first I think they’re pulling a prank on me. This wouldn’t be the first time. For a month I was getting emails from someone claiming to be my long-lost mother who abandoned me when I was born. And when I went to meet her it turned out to be Mangan and Sam, who threw a corndog at me. So you can see why I’m skeptical about this.

“Here’s the check,” says the lawyer.

I inspect it. It’s the real deal. Poor Mrs. Harper. But then again: I’ve never held this much money in my hands, especially since Disableds get paid ten cents on the dollar. I go to hug the lawyer but he pushes me off and leaves the room.

“So I guess you’re putting in your two weeks then?” says Mangan.

“I figure I’ll just quit today,” I say.

“Listen,” he says. “This business? It’s in the shitter. We’re not getting heads in like we used to. I can barely pay you guys, let alone the rent. But for a small loan we could do some renovations, buy a new sign, hire a social media manager. Then we could actually make a profit again. Positive.”

“Why would I do anything for you?” I say.

“It’s not about me,” he says. “Think of all the other Disableds here. You think they have options outside this place? You think anyone wants to hire them to serve burgers or lay down bricks? They’d be lucky to get a job with TrashLyfe® cleaning up toxic waste in the ocean.”

It’s true; this is the only good thing they have. But also: I can finally get this hole stitched up, get this QR code on my elbow removed for good.

“Take the rest of the day off and think it over,” says Mangan. “Christ do you want me to grovel? Because I’ll grovel. I’ll grovel until my knees bleed.”

On the way out I pass by Sam who’s applying vaseline to her face.

“Well looky here,” says Sam. “Mr. Big Shot got his inheritance. Well, fuck you. When the Disabled uprising happens, it’ll be your head on a pike.”

I go outside and greet the summer air. Children on skateboards fly past me like cherubs. A bluejay seems to hum a melody to my footsteps. For once I don’t feel gawked at. I go deposit my check at the bank and rush to the Abled-Now! clinic before they close.

***

“It’s really a straight-forward procedure. I’d explain in detail but you’ll be knocked out for all of it,” says the doctor.

The doctor’s name is Johann Merrick. He’s Swedish and has his framed medical degrees up on the wall, right next to before and after photos of his Disabled success stories. Some of them are really unfortunate. There’s a guy with a tumor the size of a melon growing out of his forehead. In the next he looks like Brad Pitt. There’s a girl with a pig nose and tusks growing out of her mouth. In the next she’s smiling sans tusks and has a firm Greek nose. There’s even someone born without skin on their face, now covered in fleshy afterglow.

“Don’t let those scare you,” says Dr. Merrick. “There’s pretty much nothing I can’t fix.”

“It’s not the hole I’m worried about,” I say. “It’s the QR code.”

“That’s nothing,” he says. “Legally I’m allowed to remove it with a laser right after the procedure is done.”

“And then I can go to the Abled supermarket? Cineplex? Knott’s Berry Farm? ” I say, hardly able to contain myself.

“Settle down kiddo,” he says. “You’ll be able to do all that and more. Good looking guy like you should be able to find a job, pronto.”

Suddenly the doctor’s phone rings. He answers. His face sinks. He sets it down and puts his palms up.

“It’ll have to wait until tomorrow,” he says. “My daughter slipped on the pool deck and needs me to come stitch up her forehead. Show up around noon and we’ll get you set up. Also don’t eat anything beforehand. It’ll make things a lot easier, trust me.”

***

That night I go to the Disabled Cantina for one last drink. It’s a wooden barn with plywood walls where they serve cheap beer that tastes like dishwater. I have no friends here. It’ll be an easy transition to Abled life. I don’t tell anyone about the transition. Instead I sit at the bar and renew my daily affirmations: I am an abundant source of love. The universe surrounds me with happiness. Everything I need I create within myself.

Someone spills beer on my shoulder. It’s Sam. She’s sloshed. She tries to light a cigarette with shaky hands until I grab it before she burns her eyebrows off.

“You fuck,” she says. “Mangan told us everything. So you’re just gonna let us all be jobless? Homeless? Run over in the street by some anti-Disabled lunatic?”

“Don’t act like you wouldn’t do the exact same thing in my position,” I say.

“You bet your ass,” says Sam. “Because my parents didn’t want me. Because kids threw rocks at me. Because I used to wait beneath the overpass until some perverted dad paid me to put his son’s baseball trophies up my you-know-what. But you? I always figured you were a decent guy. That’s why that Harper was always so nice to you.”

She drops her beer and it shatters all over her laceless shoes. Nobody bothers glancing over. Everyone here calls her Sloppy Sam. I used to think it was funny, but now it’s just sad. But she’s wrong; I’m not a decent guy. I’ve waited my entire life for this. Humiliated myself in front of depressed teenagers who need a reminder that their lives aren’t so worthless after all.

“I’ll see you around Sam,” I say. “Or maybe never.”

I walk out and she spats at me, totally missing.

***

The next morning there’s a phone call. It’s Tiffany. I remind her I don’t work there anymore, when she tells me that the entire building burned down.

“You might want to come look for your paystub,” she says.

When I show up everyone is standing on the sidewalk. The building is smoldering mess of cow dung. The rooftop collapsed on itself and destroyed everyone’s booths. Some of them had their stuff there, like Brady who played clarinet through the stoma in his neck. The firefighters didn’t even try to put it out. They just waited until the very last ember disappeared. Everyone is discussing how the fire could’ve started. They theorize it could’ve been a gas leak, a candle, a space-heater placed too close to the curtains.

“Bull shit,” says Sam. “It was Mangan. He did it for the insurance money.”

No one is able to reach Mangan, who according to Tiffany went to Denmark for the weekend.

“This is your fault, by the way,” Sam says to me. “If you’d been here for us this wouldn’t have happened.”

The others, now newly unemployed, ask what they’re going to do at the end of the month when they can’t pay rent and their callous slumlords kick them to the curb.

“I don’t know,” I say. I really don’t.

Then the police roll by. They pull the batons out and tell us to go back to our Designated Zones. For them it’s beneath the overpass. For me it’s Dr. Merrick’s office for our appointment.

So I wave goodbye to everyone and leave. For the last time, I hope.

***

I sit in Dr. Merrick’s waiting room. There’s a magazine advertising thyroid implants on the table next to me. Clownfish with holographic scales float in a suspended aquarium. The receptionist uses calipers to measure the symmetry of her breasts.

I get to thinking: Sam has been nothing but a bitch to me since the day we met.

But also: What about the others? What are they going to do now without income, without a purpose except being carnival freaks? Especially Sam. Someone like her would never get hired. She’s too abrasive, not the type you’d invite to a birthday party. And it’s not like any of them have references, either.

But I’ve suffered, too. I’ve suffered twenty-eight years of heckling and stares and people at the unemployment office shutting the door in my face. All the love I’ve lost, never really had to begin with. A future with kids. Homeownership. Compliments on my hair and genetic makeup.

But still.

I guess I could use my money to put everyone up in hotels. The kind that allow Disableds, as long as you tip well. Invest in a new business. A chocolate dipped banana stand, maybe. Hire my old coworkers to run it. Even Sam. Then we’d pretty much be in the same boat as before. Except with a little more dignity.

I once again renew my daily affirmations: My body is my home. My decisions are the right ones for me. You make yourself amazing.

The receptionist calls me into Dr. Merrick’s office. I walk in and there’s puzzle pieces scattered across his desk. He concentrates intensely. I knock on the threshold.

“Oh,” he says. “I wasn’t sure you’d come.”

“Here I am,” I say.

“I’ve prepped the operating table,” he says. “Say the word and the anesthesiologist will knock you out. Ready?”

I look at the doctor, the framed photo of his busty wife next to him. Out the window the world has never looked brighter. I turn around and face the door. There’s a portrait of kittens hanging from it with the caption: WHO DO YOU WANT TO BE?

And this is what I say.

Sean Nishi is a Japanese American writer from Los Angeles, CA. His work has previously appeared in Sierra Nevada Review, STORGY, Sunflower Station, Always Crashing, Bridge Eight Press, Ember Chasm, TIMBER, and Landing Zone. He lives with his cat Waffles.