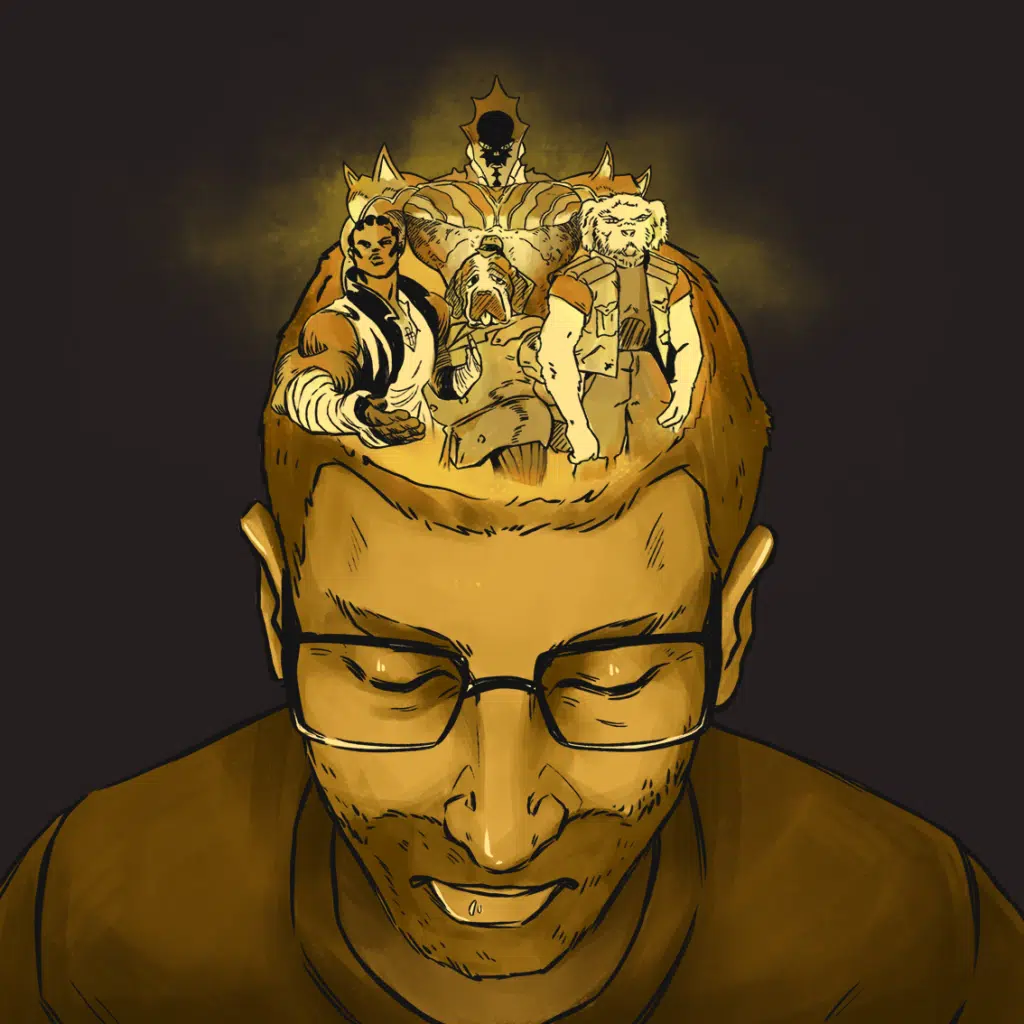

By Jean Marc Ah-Sen.

Montreal-based comics artist Al Gofa has built a career testing out creative ways to mix genres.

In his debut graphic novel Chevalier Bataille (Knight Battle,) Gofa reworked key elements of the war story until it aligned with the structure of the quest narrative. His follow-up Dark Angels of Darkness featured gladiatorial combatants sharing bodies through the esoteric art of “fusion,” and merged science fiction and dark fantasy components. Gofa is a self-professed admirer of westerns, and his comics also celebrate the indefatigable human spirit and the camaraderie that flourishes when the bonds of men are tested by external stressors.

In 2021, Gofa set his sights on starting his own publishing company called Nouveau Système (New System). After years spent freelancing, he was curious to see if the venture could help him produce groundbreaking material that other publishing outlets might balk at; the ambitious Shōnen Jump-style martial arts comic anthology Cry Punch Magazine was the company’s debut release, and featured work by artists Nick Dragotta, Amor Gavez, Linnea Sterte, David Brothers, and Mattilde Kitteh.

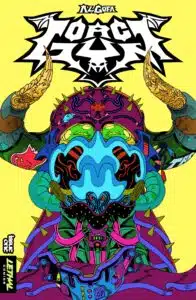

Gofa’s two forthcoming projects are the crowdfunded Orc Gym and Red Planet Blues (written by Patrick Kindlon), which are set to release this year. These comics promise to take the revenge and detective stories to new synthetic heights by leaning heavily into their action fantasy influences, and will further Gofa’s theories of comic book naturalism based on the writing of film theorist André Bazin. Bazin believed that cinema was a superior art form to painting and photography because of its ability to reproduce reality with fidelity, arguing that a naturalistic acting style that did not call attention to itself furthered this goal. Gofa’s work has transposed these ideas to the medium of comics in terms of writing, figuration, and the believability of character motivations.

I corresponded with Gofa to discuss crowdfunded publishing projects, the imperilled artistic spirit, and the “force and freedom” of making comic books about bodybuilding.

Jean Marc Ah-Sen: Although you have published comics at places like Editions Pow Pow and Peow Studio, you have recently embraced crowdfunding platforms like Kickstarter to release your books. What are the advantages and disadvantages of this developing publishing model, and do you think that it will remain a workable alternative to traditional forms of print distribution?

Al Gofa: Self-publishing offers a distinct advantage—the freedom to bring your book to the masses without relying on anyone else. For artists, this sense of independence can be liberating, even if only psychologically. It’s like a man in his forties riding a motorcycle—it gives him a feeling of freedom, whether it’s true or not. With traditional publishers, even before dealing with them and creating work on my own, I find myself adapting my ideas to fit the preferences of editors. But Kickstarter allows me to break free from those (in my case “fake”) constraints and create the work that I want to create.

But how long will this business model last? That’s a fair question. While I believe self-publishing will continue to be relevant for some time, it will never fully replace traditional print distribution. If you’re not using mainstream distribution channels like direct market or bookstores, people with opportunities or money like Art Directors, Convention Managers, Festival Juries or Publishers may view you as an “amator” and not take you seriously. Furthermore, the most successful Kickstarter campaigns have well-established webcomics beforehand or prior experience with big publishers.

Jean Marc Ah-Sen: Your latest project is Orc Gym, a fantasy comic that blends your love of bodybuilding and revenge action films. How did you hit upon this combination of stylistic influences, and what is it about a genre mash-up that you find appealing?

Al Gofa: Genre mash-ups are too easy to avoid. Adapting stereotypes from various genres is a simple way to craft a captivating narrative. Personally, I’m drawn to revenge action, crime, and thriller films. Science fiction and fantasy’s world-building approaches don’t interest me much. I prefer stories that plunge you into an unfamiliar world, yet expect you to grasp it, like watching a black and white samurai movie for the first time. These flicks feel like better science fiction to me.

Another kind of story I relish is the slow-burn, concentrating on a specialized group. [Classical Hollywood director] Howard Hawks’ setups resemble action movies, but they’re truly studies of group dynamics shrouded in well-crafted light drama. These stories feature high-stakes individuals, and while the risks are significant, the plot revolves around what it takes to be the kind of person who performs these perilous tasks. They’re not procedural movies per se, but they draw you near to the action. I also delight in procedural films like Becker’s Le Trou and most of Bresson’s works.

With Orc Gym, my aim is to examine these three narrative aspects. The tale focuses on a group of dedicated orc bodybuilders and the hurdles they encounter working together. My plan is to integrate procedural bodybuilding into a high-stakes thriller concerning money and drug problems.

Jean Marc Ah-Sen: Are you suspicious of so-called “purist narratives” or genre work that does not like to move beyond its established boundaries? Is the attractiveness of artistic discovery built around advancing new genre forms?

Al Gofa: I get what you mean, but I never thought folks would take that stance. To me, if tales keep going around in circles, it’s because the writers just don’t give a damn. It’s natural to use classical tropes, but it’s also natural for our art to converse, to have a response. So, these tropes may stir something in me, but I have to say something fresh. As a writer and artist, I’m grateful to be inspired always; to have ideas just flowing like a river. I can’t even fathom not standing my ground and claiming my creativity. Some of us may not be as jazzed about the popular tropes, and that’s alright. It just means we have a conversation going with a smaller group, but we’re still “shooting back.” That’s what writing is to me.

Jean Marc Ah-Sen: A lot of your comics deal with spiritual and bodily perfection, as well as the machismo of brotherly fraternities. Are these playfully ironic explorations of friendship, or are they celebrations of homosocial bonding and family?

Al Gofa: I am not sure about spiritual perfection, but bodily perfection—now that’s a different story. There are plenty of reasons why I’m drawn to it. For one, I love the way muscular bodies look when I draw them. There’s something mystical about these figures, suggesting a level of heroism beyond the norm. It’s a bone I throw to myself and my readers, and I’d chase after it anytime. The fantasy of force and freedom is just too alluring.

As for the homosocial group, it’s a topic that’s close to my heart. Growing up in a small town in Quebec, things were pretty Catholic and stereotypically American. Women were a mystery to me, and most of my bonding was with other boys and men. The dynamic with girls was just too different. Exploring the qualities and problems of male friendships is something that fascinates me.

So yes, in my stories, the focus is on male relationships, while female characters take on supporting roles. So far, they’ve always been about groups of men working together to achieve a goal. And the key to portraying these relationships is through dialogue: witty conversations, playful insults, and friendly jabs create a sense of intimacy and camaraderie between characters.

But it’s not just words that bring these relationships to life. Physical contact and touch are essential in expressing emotions and creating connections. This approach has helped me explore the complexities of male relationships, and I think it shows in my writing. So there you have it—an emphasis on male bonding and relationships, conveyed through dialogue, banter, and touch. It’s all about exploring the intricacies of male friendships.

Jean Marc Ah-Sen: Comics are often touted for their ability to transcend genres and their unparalleled storytelling potential; in spite of this reputation, so much of comics can be marked by conservatism and an unwillingness to deviate from ideas that are commercially entrenched as profitable. How do you negotiate these very different understandings of the medium in your own work?

Al Gofa: It’s a struggle, isn’t it? Even indie publishers fall prey to a conservative approach. They have a preconceived notion of what “indie” should be, and it’s stifling to new artists. I’m not sure if publishers are more conservative now than they were before, but my favorite current artists aren’t working for mainstream publishers.

Most of the comics I enjoy were created by older or deceased artists who once worked on big hits. Nostalgia has nothing to do with it; if I were nostalgic, I’d be animating in the style of Disney. I care for new work, just not mainstream.

But let’s consider the hypothetical scenario of Frank Miller as a young artist presenting Batman: The Dark Knight Returns to current editors. Would they accept it? I don’t know. What I do know is that there are plenty of talented artists out there, and editors have no idea where to look for the next great book. Frankly, I don’t understand what editors want.

If I were an editor at the Big Two [Marvel and DC Comics], I’d close all ongoing projects and commission Olivier Schrauwen for a Wolverine comic, Daniel Clowes for a Doctor Strange comic, Yuichi Yokayama for a Hulk comic, Linnea Staerte for a Swamp Thing comic, Manuele Fior for a Batman comic, Andrew Maclean for a Green Lantern comic, and Connor Willumsen for an Iron-Man comic, and so on.

In short, I don’t compromise in my work. The minute my bank account is low, I go get a side job, but that doesn’t stop me from pursuing my artistic vision.

Jean Marc Ah-Sen: What is the trend that you hate the most about contemporary comics? What facet of comics production is the most rewarding, renewing your faith in it on a regular basis?

Al Gofa: Maybe it’s just me, but it seems like there’s a proliferation of artists using 3D models and tracing over them these days. It’s like every fourth comic is a CGI abomination. Honestly, I’m just not feeling very inspired by what’s going on in the scene right now. I do appreciate small press publishers like Peow Studio, Breakdown Press, and Koguchi Press, but let’s be real—they’re small press.

I had a good hit with Dark Angels of Darkness, a 200-page book I wrote, drew, lettered, and coloured myself, which netted me $7000 CAD. I’m grateful for the recognition I’ve received from my superfans, who are mostly pros in the animation and comic book industries and fellow artists, but let’s face it, producers, editors, and art directors don’t give a damn if I’m to their artists’ tastes. I can’t shake this nagging feeling that we artists aren’t taken seriously. I’ve had really big names in the arts recommending me to their editors or art directors many times and it never amounted to anything. I am sure I am wrong because I know nothing, but I feel that if a writer or an editor was recommending me, then, somehow, that would be different.

Small press is a fun diversion, but it’s not a serious pursuit and won’t lead to bigger and better things. It’s unfortunately not renewing my faith in the comics industry.

Jean Marc Ah-Sen is the author of Grand Menteur, In the Beggarly Style of Imitation, and the forthcoming Kilworthy Tanner. His work has appeared in Literary Hub, Catapult, Maclean’s, The Globe and Mail, The Toronto Star, Hazlitt, Maisonneuve, and elsewhere. The National Post has hailed his writing as a “an inventive escape from the conventional.”