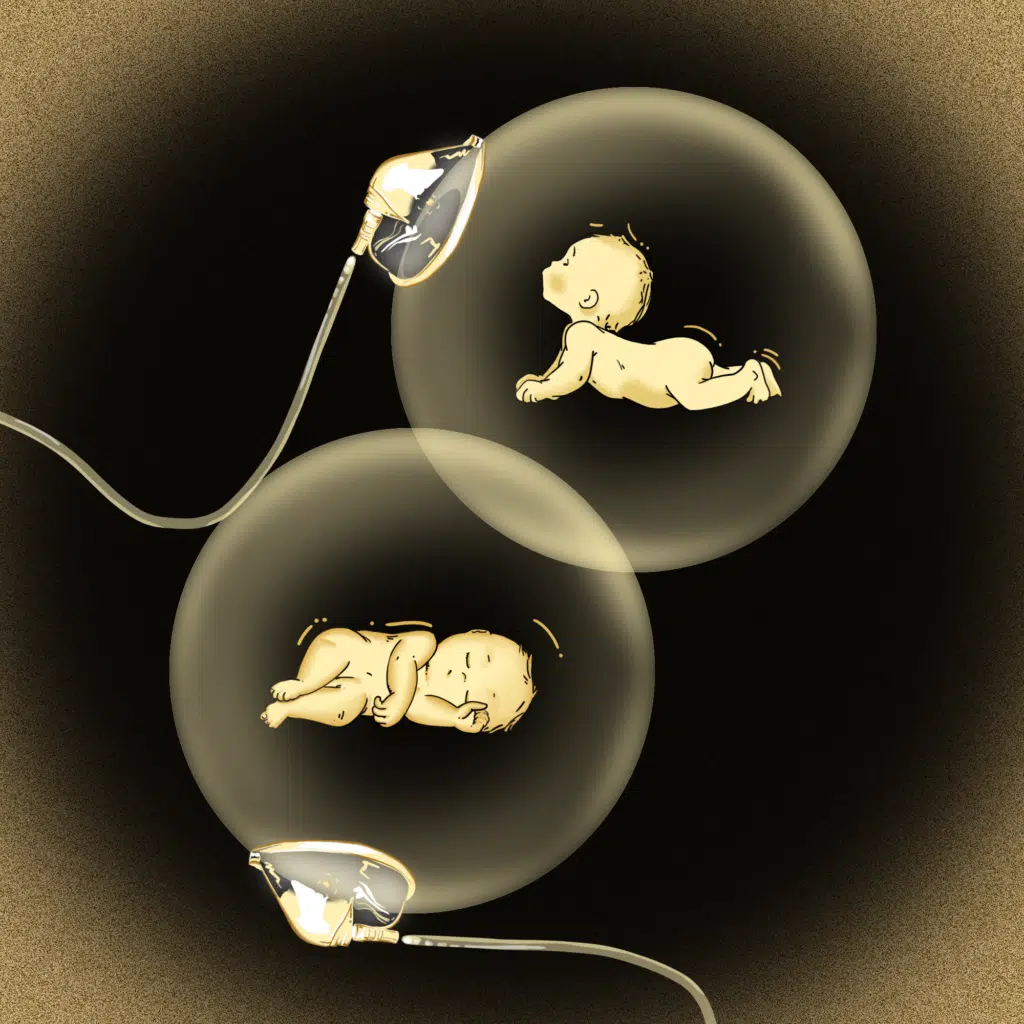

Call it baby bust and oldster boom — two trends that signal a demographic transformation without precedent in human history.

In much of the world, declining birth rates and longer life spans are combining to create a phenomenon demographers call global aging. It brings both problems and opportunities that are hard to fathom and require rethinking the way societies are organized and economies are run.The world’s population of people over 65 is forecast to double by 2050. By that time, a quarter of the people in developed countries will be that age or older. No country has fully figured out how to cope with steadily rising expenditures for the pensions and healthcare of the swelling ranks of senior citizens.

According to United Nations projections, the age group most in need of support — those over 80 — will triple by 2050.

“Unlike other long-term predictions, there is nothing hypothetical about this,” said Richard Jackson, president of the Global Aging Institute, a Washington-based think tank. “This is as close as social science comes to a certain forecast. Absent a Hollywood catastrophe like a colliding comet or an alien invasion, it will surely happen.”

In China and the U.S., population growth is slowing.

The slowing pace of population growth was thrown into sharp focus by data recently released by the world’s two biggest economies, the United States and China. And birth rates have been dropping elsewhere, with the exception of sub-Saharan Africa.

In April, the U.S. Census Bureau reported that America’s population growth in the past decade slowed to its lowest rate since the 1930s. China, which also conducts a once-in-a-decade census, reported the lowest rate since the 1950s.

The statistics so alarmed the Chinese government that on May 31 it announced that married couples would now be allowed to have three children — a striking reversal from the “one-child policy” the Communist authorities introduced in 1979 and amended in 2015, when two children were allowed.

Experts view the reversal as an implicit admission that China’s decades-long programme of social engineering has failed.

The rationale for restricting the size of families was to ensure that population growth did not outpace economic development in what was then, and still is, the world’s most populous country.

Humanity has never faced the challenge of global aging before.

Although global aging will have a decisive impact on the 21st century, it does not often make headlines. Unlike climate change, global aging and shrinking population growth have failed to fire the public imagination.

But signs of the trend — fewer babies and longer life spans — have been obvious for years.

One of the demographic milestones that did make headlines came from a Japanese retail number: In 2012, adult diapers for the incontinent elderly began outselling baby diapers. That underscored Japan’s status as the country with the world’s longest life expectancy — 84.3 years — according to the World Health Organization.

Humanity has never before faced this kind of challenge. “For most of history, the elderly accounted for a small fraction of the population, never more than 5% in any country,” according to Jackson. That began to change after the 19th century industrial revolution and major achievements in medicine, including a sharp reduction in the number of children dying before their fifth birthday.

In discussions about the end result of the demographic transformation now in progress, two long-range forecasts that proved spectacularly wrong tend to come up.

One was by the 18th century English scholar Thomas Robert Malthus and another by Stanford University professor Paul Ehrlich. Both predicted that population growth would outstrip food supplies and result in world-wide famines.

In 1968, Ehrlich published “The Population Bomb,” a book that said “hundreds of millions of people are going to starve to death” in the 1970s and urged action to keep birth rates down. The book sold millions of copies and stirred world-wide fears of overpopulation.

World’s nations have trouble boosting birth rates, coping with elderly.

Since 1968, the world’s population has more than doubled. It now stands at 7.9 billion and is still growing, although at a sharply lower rate than in the past. And although there have been famines, mostly in Africa, the world did not run out of food, thanks partly due to innovations in agriculture such as better fertilizers, improved seeds and drip irrigation.

While countries have adapted to the food needs of rising populations, they face problems boosting their birth rates and coping with growing cohorts of the elderly.

Rewards to entice couples to have more children do not appear to be the answer. In Russia, whose current population of 146 million is expected to shrink by 30 million in the next three decades, the government offers cash incentives and washing machines to new parents, but birth rates continue to decline.

“You can’t bribe women to have children,” said the GIA’s Jackson. In his view, the most important response to fewer babies and longer life spans would be “productive aging” — keeping older people in the work force for longer.

A big obstacle to that in many developed countries is the age — usually 65 — at which government or corporate pensions kick in. The concept of financial support in old age dates back to 1881, when the German statesman Otto von Bismarck introduced it to Germany’s Reichstag.

It was originally pegged at 70 years, roughly in line with life expectancy in Germany at the time, and later lowered to 65. America’s Social Security Act of 1935 set the retirement age at 65. As Jackson sees it, this is a policy that pushes older workers into premature retirement.

For rich countries, one way to balance the age distribution is to open the door to young immigrants. But with anti-immigrant sentiment running high in much of Europe and the United States, immigration reforms are a thorny issue. It’s where, as Jackson put it, “economic logic collides with politics.”

Bernd Debusmann is a former columnist for Reuters who worked as a correspondent, bureau chief and editor in Europe, Latin America, the Middle East, Africa and United States. He has reported from more than 100 countries and lived in nine. He was shot twice in the course of his work – once covering a night battle in the center of Beirut and once in an assassination attempt prompted by his reporting on Syria. This analysis was originally published by News Decoder.